In-house solicitors thematic review

14 March 2023

Executive summary

Read summary report into the challenges facing in-house solicitors

More than 34,500 in-house solicitors now work in more than 6,000 organisations across England and Wales in a wide range of industries and public bodies. These range from multinational corporations and government departments to high-street businesses, charities, educational establishments and local health authorities.

This important, influential, and diverse part of the profession plays a key role in helping organisations to behave legally, fairly and ethically.

General Counsel in particular is an important leadership role in organisations. It's a role that often combines both trusted adviser and business partner which helps to drive the strategic direction of organisations. This provides in-house solicitors with even greater opportunities for influence but also presents more challenges.

Recent highly public investigations have highlighted the risks that can arise if the client's best interests are not balanced with the public interest.

Our review showed that most in-house solicitors felt positive about their role in organisations and also felt that their legal function was valued. However, solicitors also highlighted significant political and economic pressures, increasing workloads and challenges in retaining and recruiting talent.

For these reasons, without adequate safeguards and systems in-house teams may struggle to manage conflicting duties and ethical and regulatory risks. They must, therefore, carefully consider how they can deliver organisational objectives while maintaining independence.

Why we did this review

We wanted to better understand the role of in-house solicitors, in particular:

- How they support an ethical culture in their organisations

- The challenges they face in meeting their professional obligations

- How we can help support in-house solicitors.

This report draws on their experiences and highlights where additional support or actions are available or may be needed.

What we did

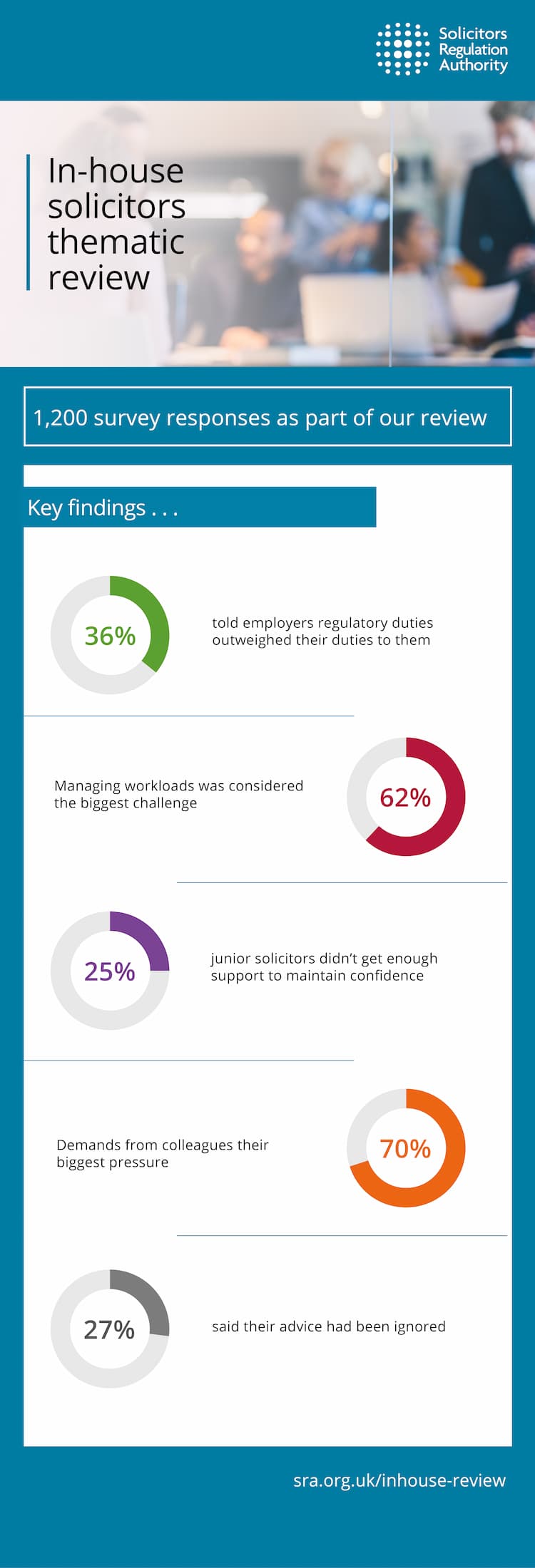

- Considered more than 1,200 survey responses from in-house solicitors (respondents)

- Conducted in-depth interviews with in-house solicitors in public and private sector organisations

- Met with stakeholders in the in-house sector.

Key findings

We identified these key findings:

1. Safeguarding independence

Overall, in-house solicitors are in a good position to withstand pressures that could affect their ability to provide objective and impartial advice. They reported that their independence was highly valued by organisations as it provided a different perspective when making decisions.

However, we identified that some in-house solicitors may not have the support and internal controls to maintain their independence. This may be particularly risky where the commercial interests of the organisation are not in alignment with regulatory obligations. For example, 5% of respondents had been pressured into suppressing information that conflicted with their regulatory obligations.

Read more about safeguarding independence

2. Managing risks with policies and controls

Our review found many in-house teams did not have dedicated policies and controls to record and report legal risks, manage conflicts and confidentiality or instructions. In several cases there was also an over reliance on ‘common practice’ to manage regulatory issues.

This could mean some teams are not adequately prepared to spot risks and manage pressures. More positively, we also noted that junior solicitors were well supported by managers and had a good level of awareness of reporting systems.

Read more about managing risks

3. Managing pressures and meeting regulatory obligations

More than two thirds of respondents said demands from colleagues was their biggest pressure (70%). However, most felt comfortable advising their employer they could not take an unethical course of action. They also felt confident they could act ethically under pressure.

A minority had experienced significant ethical and political pressures. This included 10% who said their regulatory obligations had been compromised trying to meet organisational priorities. If the right controls are not in place and pressures are unmanaged, it could lead to unethical behaviour.

Read more about managing pressures

4. Maintaining continuing competence

One in 10 respondents felt they did not have enough time to maintain their continuing competence. We also saw that senior leaders did not always reflect on learning needs and regulatory obligations appropriately.

Interestingly, most junior solicitors self-managed their training and 25% had not received training on professionalism, ethics, or judgment within the past 12 months. All in-house solicitors must make sure they have the opportunity and time to reflect on their continuing competence.

Read more about maintaining continuing competence

5. Ethical leadership and ethical risks

Identifying ethical risks and regulatory challenges could be more difficult for in-house teams when under pressure and without suitable infrastructure that puts ethics firmly on the agenda. However, some senior leaders did not see ethics as important or did not regularly discuss these risks with the legal team.

We also saw examples of in-house solicitors using their influence to champion ethically, socially, and environmentally supportive initiatives. At the heart of this leadership was a feeling of responsibility as the ethical conscience of their organisation.

Conclusion

While the in-house sector is currently facing significant scrutiny, we saw evidence that it adds considerable value to organisations and the wider legal community. It has a unique understanding of its client’s needs which helps it to connect the dots between legal advice and ethical leadership. However, it also faces a number of challenges.

Many in-house solicitors described experiencing commercial and political pressures and professional isolation. We were also concerned that in most teams there were some weaknesses in policies and controls which would help them to oversee and identify risks.

In particular, we noted that balancing regulatory responsibilities and independence while safeguarding effective working relationships could be challenging. These challenges may be exacerbated if in-house teams have limited resources and a lack of focus on ethics in day-to-day learning and work activities.

In-house solicitors should take steps to reflect on their approach to identify and manage ethical risks and assess whether they are meeting their regulatory responsibilities.

If there are areas for improvement in-house solicitors should discuss this with employers and explore how they can support the organisation as well as the legal function. Dedicated policies and tailored shared controls will help legal teams and employers to manage these risks together.

Practical help and guidance

We are committed to continuing to support the in-house community. To respond to the issues raised in this review we are developing further resources for in-house solicitors and their employers. These include:

- A series of events focusing on key themes and issues for in-house solicitors

- New resources on our website for in-house solicitors and their employers

- New guidance materials on key areas such as competence and knowing your client.

You will also find some helpful resources and information within this report including:

- Next steps and checklists

- Case studies

- Good practice examples

- Information for in-house solicitors and their employers.

Findings

What we expect

In-house solicitors must comply with the standards under our Code of Conduct and Principles. These set the fundamental rules of ethical behaviour we expect in-house solicitors to uphold. Principle 3 sets out that solicitors should act with independence, and this includes independence from a client.

The risk

In-house solicitors must act in the best interests of their client. However, where there is a conflict between the client’s interests and other principles, those which safeguard the wider public interest take precedence over a client's interests. For example, upholding the rule of law and public confidence in the profession.

Maintaining independence and managing work when duties conflict is a fundamental part of legal professional ethics. It can be particularly challenging for in-house working relationships when an in-house solicitor’s advice does not support the business' objectives.

Roles and partnerships

Senior in-house solicitors had a range of roles and responsibilities including corporate governance and compliance roles, for example:

- they managed external advisers

- were line managers

- were legal directors

- sat on senior management teams and executive committees

- acted as company secretaries supporting board agendas.

These roles help senior leaders to build effective relationships with colleagues, understand the business and its priorities. In some cases this also extended to influencing the board or even making commercial decisions in executive teams.

Senior leaders frequently told us they saw their role as business partners who enabled organisations to achieve their objectives by solving problems. They highlighted that it was important to establish professional partnerships to understand the business and get early involvement in projects.

One General Counsel in the private sector, said: 'We are legal business partners not just a support function and our 'USP' is driving the success of the organisation through our shared vision and understanding of the business.'

This was viewed as a benefit because it managed legal risks and provided 'a seat at the table' and early involvement in projects.

Many senior leaders also told us they had an informal veto over decisions. While for most participation in board meetings was limited, they indicated they had an opportunity to 'positively influence behind the scenes'.

Roles in governance and building effective partnerships with colleagues undoubtedly has benefits for both the legal function and the organisation. In particular, a senior leader in the public sector said that as a solicitor they provide a unique and independent perspective in executive teams. They have a wide-angle lens view over the whole business because their role engages with so many parts of the organisation.

Crucially independence means that solicitors can provide trusted advice that is not influenced by personal or commercial interests. Several in-house solicitors highlighted that this role was highly valued by other senior leaders and provided a unique perspective when managing risks.

For example, a private sector General Counsel said: 'Being in the GC 100 and other organisations helps to get an external perspective to remind you about the value of objectivity as a mindset. The chief executive officer has also said they value this in the organisation because group think isn't valuable.'

Managing risks to independence

However, in certain circumstances maintaining independence and managing working relationships can be more complex. Just over a third of respondents (36%) had experienced telling employers about the priority of wider regulatory duties.

Some senior leaders also recognised that balancing regulatory responsibilities day to day while maintaining effective working relationships could be challenging.

As one senior leader in the private sector notably said: 'Working in-house is a marriage not a fling. It can be hard to maintain independence when you are an employee, particularly if you feel like you are going against the will of the organisation. This dynamic can make you feel more vulnerable as it's harder to walk away.'

We asked in-house leaders what steps they had taken to maintain independence, and some identified that this was largely supported by governance structures. For example, direct reporting lines and access to the board and Chief Executive Officer (CEO), whistleblowing procedures and organisational speak up policies.

A General Counsel in the private sector said: 'It helps that we are a central team and the GC reports to the CEO. We have our own legal budget and no financial targets. We report up to the board to push issues up as necessary.'

However, many senior leaders saw independence simply as an intrinsic part of their role. While ethical values and independence can seem simply necessary and natural, balancing regulatory obligations with commercial or even personal interests can put this under pressure. This is when conflict could arise and all in-house solicitors need to be aware of the risks so that they can be prepared for them.

Team structures

Most respondents and most senior and junior solicitors (60%) said they worked in a central team. In-house leaders frequently saw this as a way to maintain their independence. However, some acknowledged that this had drawbacks in terms of early involvement in projects and discussions unless teams managed this proactively.

Just under a quarter of teams had individual solicitors embedded in project or operational teams in other departments, locally or internationally. This helped departments access advice more easily and helped legal teams to have effective working relationships.

A General Counsel in the private sector said: 'If people know who we are, they can approach us and come to us earlier.'

However, while this has obvious commercial advantages, embedding solicitors in mixed teams can pose risks to independence if they are isolated from the legal team without adequate supervision and support. Many senior leaders had taken steps to manage this risk. Most teams operated on a hybrid basis with a central team and some individuals allocated to sit directly with project teams for the duration of a project.

One private sector General Counsel said: 'We use a hybrid model to get a greater level of independence from the client and better oversight and accountability with all of the benefits of being close to the business so that we can be more agile and responsive.'

A junior solicitor we met described being embedded in a project team with a non-lawyer manager. They noted that it was difficult to obtain support to push back when being asked to carry out tasks beyond their competence. Senior leaders in the legal team responded by changing the structure of the team to maintain close supervision and support. Individuals known as 'legal business partners' still sit with different teams but reporting lines now remain direct to General Counsel.

A senior leader in a public sector organisation said: 'We still have people who service project teams but they are closely supervised by a solicitor, so they are not isolated and still feel part of the team. It's a useful model because the pace of the projects is very quick and it's easier for them to absorb information and otherwise they wouldn't have visibility. However, we also recognise the risks, particularly for junior solicitors. It's about safeguarding our lawyers to ensure they can stand up for what's right.'

Financial independence

A significant number of in-house teams in the private sector had rewards or bonuses linked to the commercial success of the business (80%). This could pose risks in terms of maintaining independence and managing ethical pressures, so we asked leaders if they had any concerns. Most disagreed.

Generally this was because it was not the main way they were remunerated or because bonuses were usually based on performance or other organisational successes. However, many bonuses were in some way linked to the success of the company.

Typical responses included:

- 'No because it is based on a group level and a small percentage depending on your level. This then filters down to individual performance levels based on merit.'

- 'For most roles there is a bonus and only 40% of it is linked to the financial performance of the business.'

- 'We have a bonus system loosely tied to company performance but it's not the main part of remuneration. Even when the company makes a loss we still get a bonus. So, this isn't really a conflict'

In most cases this may not be a risk. That is unless a large part of remuneration is linked to profitability or bonuses are not paid if the organisation is less profitable. In that case in-house teams may need to consider whether this could compromise their independence.

Panel firms and independence

External firms are often an important resource for the majority of in-house teams. The main reason for instructing external solicitors was for:

- specialist skills or advice

- need to manage resources or volume of work in a cost-effective way.

Over half of in-house teams worked with a panel or roster of external firms. Others said that they preferred to be flexible and select trusted firms based on the work needed.

Strong working relationships with firms, loyalty, understanding the culture and how to deliver business friendly advice were all highly valued by in-house leaders.

To support shared knowledge as well as dedicated resources, some encourage secondees from firms to join their teams. This means that legal services can be closely attuned to the commercial objectives of the business and provides secondees with wider work experience.

As well as understanding the commercial aspects of the organisation better, some firms also provided training and access to resources and systems. Two in-house leaders also mentioned that firms were valued for providing an opportunity to keep up with best practice, as they work for other clients.

Considerations about fixed costs and whether services offered value for money was also an important factor, particularly for public sector teams. However, just 37% of in-house teams had a specific policy or guidelines about appointing external firms.

Therefore, some in-house teams retained very large panels, for example, one team had a roster of 60 firms. They told us they were trying to improve policies and procedures by introducing panel reviews, identifying key users, and helping them to understand who they can instruct and the cost.

Panel review procedures

Most panels were reviewed every two to three years or they were regularly invited to tender or pitch for work. Reviews were an important way to check for conflicts, assess the value of services and test firms for fit in terms of ethos, sustainability and diversity and inclusion.

However, we noted that even teams with large panels who carried out reviews tended to use the same preferred firms for long periods. Twenty-five per cent preferred to use one trusted firm because they valued the long-term working relationships they had and their knowledge about the business.

A General Counsel explained the typical benefits this provides: 'Most firms have been on the panel for ten years, but we review them every three years. I believe long relationships are better because we are a complex organisation, and they understand us better. This is also why we like to take secondees who then go back to firms - so we can work faster.'

Conducting regular reviews and refreshing tenders is a useful way to ensure firms’ legal services still meet the needs and budget of the organisation. It also provides a crucial opportunity to assess how locked in firms and teams are to secondments and identify any conflicts or risks to professional independence.

One General Counsel in the private sector said: 'We review our panel every year because we have ten firms and need to look how much work is going where. We also have secondees and had to review a potential conflict, so reviews are very important.'

Support from external advisers

External solicitors also had an assurance role by providing a second opinion, challenging assumptions, or adding weight to General Counsel's advice. Senior leaders said:

- 'It is useful to reassure the CEO or Board that the recommended option is the preferred option. It can also help frame the issue for the Board. We have a house style, so it is good to get somebody else's perspective sometimes.'

- 'We seek external views for significant projects to make sure we are keeping up with best practice. We often do things for the first time and if it is a complex matter, we get a second look to test our assumptions.'

Some senior leaders also relied on external advice for reassurance and to manage feelings of isolation. A private sector General Counsel said: 'Sometimes I need to get a different view as being the GC of large team can be lonely. I need to discuss things with an external firm who might be more objective.'

Next steps to consider

Solicitors at any level may need to receive professional support. However, they should also consider whether there are any risks that professional relationships could become too co-dependent and if this is in the best interests of the client.

For example, an over reliance on secondees who are embedded in teams for long periods, or on additional services could potentially lead to risks such as conflicts or compromise independence.

This risk can be mitigated with policies and procedures that set out the parameters of shared staff and services. For example, how secondees will be supervised and guidance for employees on managing regulatory risks.

Checklists

Have you applied any of the following strategies to respond to risks around independence?

- Develop, review, or improve policies for instructing external firms, setting out responsibilities and approval requirements.

- Identify key employees, current panel members, their specialisms and have an objective and independent process to select them.

- Develop guidance that sets out the purpose and parameters for secondees joining in-house teams or in firms. For example, how any risks and conflicts will be managed and how roles will be supervised and reviewed.

What your employer needs to know

In-house solicitors are subject to our Code and Principles. These include obligations to act with integrity, in the best interests of clients and with independence. Setting mutual expectations of roles, specific regulatory obligations and agreeing where support may be needed, can aid understanding for the organisation and legal employees.

Where you and your employer can find help

- Read our guidance for unregulated organisations that employ solicitors.

- Read our risks to independence case studies

Read information from the Law Society on secondments

What we expect

Solicitors should exercise their own professional judgment when applying our Standards and Regulations in the workplace, depending on their role and responsibilities. However, they must be able to justify their decisions and actions to demonstrate compliance with their obligations. This includes duties in a conflict of interest, or when managing confidentiality and disclosure.

In-house solicitors must report promptly to us or another approved regulator, any matters they reasonably believe are capable of amounting to a serious breach. They must also act in their client's best interests and only on their instructions, or from someone authorised to provide them on their behalf. If there is reason to suspect that instructions do not represent their client's wishes, they must not act.

The risk

While in-house solicitors are not required to have specific controls or systems and procedures, they must demonstrate compliance with their regulatory obligations and justify their decisions. A lack of controls around instructions could put the legal function at risk of being unfairly pressured by colleagues who may not have authority to instruct it.

They also risk acting outside their competence, not understanding their duties in terms of conflicts and confidentiality, or the risk level of instructions. Two key aspects to managing this risk are:

- Improving the way instructions from the client are received

- Implementing procedures to monitor, track and report legal and ethical risks.

Receiving and allocating instructions

On a day-to-day basis, the legal function can be instructed by a range of individuals and business units within an organisation. Therefore, it is vital to establish and manage expectations about how instructions are received, legal advice is provided and where different interests and duties may apply.

Most in-house leaders told us that identifying the client was straightforward as it is their employer. However, some in-house leaders mentioned that this can be more difficult in large or complex organisational structures. This is because, depending on the matter, clients can include a range of individuals or entities.

We asked teams to show us evidence of any specific policies, controls, or procedures for accepting instructions. Most had informal procedures, but this was an area that some agreed would benefit from some formalisation.

For example, one General Counsel in the public sector said: 'We manage this by practice rather than policy but it would be a good idea to articulate it. People do not always understand that the person sitting in front of them may not be the client and employer.'

Most senior leaders said their instructions came from the CEO, followed by senior managers or the executive management team. Over half of instructions for teams came from a variety of employees from any level in the organisation.

Processes for allocating instructions varied in formality from heads of teams allocating instructions from a group inbox or case management system to individuals in teams approached directly for advice by email or in person on an ad hoc basis.

A junior in-house solicitor whose role included a lone shift as a duty officer for a large operational team could be approached for urgent advice at their desk or by email at any time. They told us that they could always 'refer up' if they needed support.

Another told us that they enjoyed the flexibility of being in-house: 'The culture here is that they want you to feel autonomous by nature, so work is allocated to your level and is very fluid depending on the nature of your role.'

Nevertheless, senior leaders should consider whether there are ever circumstances teams could be asked to give advice to individuals who are not the employer or whose interests are not aligned with the employer. For example, an in-house solicitor said: 'An individual in another team sometimes tries to instruct us directly to do something. I have to remind them that we are here to protect the council - not act according to their personal wishes.'

Our review highlighted that some in-house solicitors had experienced challenges managing instructions. Some 16% of senior leaders had experienced difficulty managing pressures to act in the interests of someone other than their employer.

Examples included requests for advice where in-house solicitors had to consider whether interests aligned or diverged, such as from:

- associated joint venture companies

- international subsidiaries

- senior shareholders.

Similar concerns were echoed in comments from survey respondents, including:

- 'The CEO considers all the executive team are his advisers, rather than advisers to the company. There is a subtle but important difference. We must constantly remind ourselves who the real client is.'

- 'There was an expectation that I would also advise another, separate trust. I had to explain that I was only able to advise the trust that I am employed by.'

Most in-house teams recognised that managing instructions could be a challenge for teams, particularly if they had to say no. Many also agreed that a formal policy setting out terms of engagement would be beneficial. A senior leader also further highlighted that adequate support, supervision and oversight were an important part of managing instructions:

A General Counsel in a public sector organisation said: 'This is a supervision and constitutional point as well as about how we allocate work. We need to make sure solicitors are asking the right questions to the right decision makers. That means we need to know who they are and make sure the right people are in the room when making decisions.'

Three in-house teams had developed formal policies and processes for identifying the client and allocating instructions. Policies included information about roles and responsibilities, joint expectations about when advice should be obtained and how legal risks were managed and assessed.

One team had developed an impressive, tailored platform and process, highlighted in the case study below.

Case study: receiving and risk assessing instructions

An in-house team at a large broadcasting company developed a suite of risk management systems. The system included a bespoke matter management system with an integrated portal they described as a ‘legal front door’ for file inception.

Instructions received through the portal are risk rated and high-risk matters are flagged to supervisors or if necessary senior leaders. This was supported by a legal risk register owned by the team and a process for passing high risk matters for review and sign off.

Their General Counsel said: 'We act as a mini firm of a solicitors first and foremost and offer a professional service. We are clear our advice is for the employer not the individual colleague. We are very clear we cannot sign off documents we have not reviewed if we are not part of the decision-making process.'

In terms of risk management, we noted this team had a good level of oversight of work and decision-making procedures were understood by the rest of the business. Agreeing business wide practices such as attendance in project meetings, sign off processes, roles and responsibilities ensured decisions were made with the right people.

Next steps to consider

Agreeing formal terms of engagement could help manage this risk so that employees or other parties understand how to instruct and work with the legal team.

Managing conflicts of interest and confidentiality

Linked to knowing your client is understanding where conflicts may arise and who the duties of confidentiality are owed to. This may occur for example, where the interests of individuals or the entity are not clear, or where in-house solicitors are asked to provide advice to colleagues in confidence.

Forty per cent of in-house leaders felt that there was no risk of a conflict arising in their teams, because they only have one client – their employer. However, we noted that some organisational and management structures, particularly in large corporate organisations could be very complex. Therefore, there may be circumstances where there is a risk of dealing with the conflicting interests of more than one corporate client at the same time.

A small minority (5%) of respondents reported experiencing pressure from colleagues not to disclose information that was not in the best interests of the client. However, comments were concerning and included:

- 'Sensitive data was sought by someone in a senior elected position that potentially conflicted with the best interests of the corporate client. I felt some pressure to frame my advice in a particular way.'

- 'We came under pressure to progress a project as 'standard business practice' when there were potential bribery and other financial risks. We took the opportunity of instructing our external lawyers to assist with the project. [This was] so their regulatory and compliance teams got involved...to ensure the project was fully vetted before it proceeded any further.'

In-house solicitors should also consider whether there is a risk of a personal conflict in any of their dealings. This is because, as employees, their personal interests may also be tied to certain colleagues or the interests of employer organisations.

Most in-house leaders had access to company-wide registers for personal conflicts and had a conflicts policy which was used in limited circumstances, for example when outsourcing work or for senior staff. But most teams indicated that dedicated systems were not necessary as this issue arose so infrequently.

One public sector General Counsel said: 'We anticipate conflicts with other lawyers. We just need one system and to articulate what people should record so people know their obligations. I don't think registers would work because it's a governance sledgehammer to crack a nut as it would be used so infrequently. If it's important it should be in writing.'

For some roles and in some circumstances, conflicts may not be a significant concern, however in-house solicitors should always consider whether they can justify decisions.

Understanding confidentiality risks

Many teams had implemented specific procedures to manage confidentiality risks, and most teams also had annual training on confidentiality to make sure teams understood their obligations.

However, just 10% of teams kept a policy setting out confidentiality and disclosure duties. An in-house leader in the private sector, said: 'We just expect solicitors to understand their duties of client confidentiality and we had a seminar on legal professional privilege.'

As both a legal and a regulatory obligation, it is important to understand how specific duties of confidentiality and disclosure apply in different circumstances.

In-house solicitors could explore the types of issues they have seen in their organisations, in team meetings by discussing practical scenarios where confidentiality might be breached. One team highlighted that relying only on employment contracts to manage confidentiality had exposed their organisation to regulatory risk.

A General Counsel in the private sector said: ‘We include a confidentiality clause in employee contracts and have bespoke training on confidentiality duties with employees starting or leaving the company. But we don’t have a dedicated confidentiality and disclosure policy. This would be useful as there have been occasions that former employees have joined organisations acting for the other side on a deal.’

Good practice

Some teams had developed dedicated conflict of interest checklists and policies. These set out when solicitors could act for distinct groups within the group structure. And a formal process for disclosing conflicts with suppliers when instructions were allocated. If there is a conflict, they are advised not to act, or that they should seek external legal advice.

Identifying risks

Ethical issues can present themselves during legal work but also more widely in the direction or decisions taken by the organisation. Monitoring and recording risks are an essential way to identify any actual or potential legal risks to organisations, as well as manage regulatory and ethical responsibilities.

An important element of this is the obligation to promptly report any facts or matters that could amount to a serious breach of regulatory arrangements.

Respondents ranked ‘identifying and reducing legal risks’ highest as the way they delivered value to their organisation, followed by their knowledge as a legal adviser. However, most in-house teams did not have any specific policies and procedures to identify regulatory or ethical risks.

Almost all in-house teams did not keep central records of any actual or potential regulatory or ethical risks (90%). Just one team said they had made a report to us about a potential regulatory breach. This was resolved by contacting our Professional Ethics helpline for advice.

Typically, many teams relied on individual solicitors keeping personal records and referring issues to line managers, compliance departments or whistleblowing lines. Some senior leaders described managing risks by common understanding or practice. For example, a General Counsel said: 'We have informal ones, but we are reliant on people reporting things to us and people know this would be with their line manager. A legal policy or document to let people know what to do and look out for would be good.'

The legal function should make sure it is able to identify trends or patterns of risk and training needs. For example, by implementing clear reporting protocols and having suitable oversight of matters and instructions with systems and regular structured supervision.

This risk was brought into sharp focus by a survey respondent who commented: 'Often feel pressure just to get agreements out of the door, and it can be difficult to get non-lawyer colleagues to provide straight answers to a question. You do often feel that you might not be getting the full picture and might be exposing the firm.'

However, in most cases, senior leaders told us issues and concerns could be referred up to heads of teams or team leaders. Most individuals were also clear about how organisation-wide 'speak up' campaigns could be used to report issues.

An in-house solicitor said: 'The company has a 'Speak Up' campaign. On the intranet there is a button to click to report an ethical issue anonymously. It then goes to the compliance team for investigation. I can also let my line manager know of any issues.'

Junior solicitors reported they would feel comfortable raising concerns because they had an open and supportive culture and managers, but that ethics was rarely relevant. It is important that in-house solicitors can recognise ethical risks so they can resist pressure to condone, ignore or commit unethical behaviour.

Typical comments from junior solicitors included:

- 'I feel comfortable speaking with colleagues I have known for years and have support from my line manager and the head of team. There was a time when somebody in another team signed a statement of truth setting out information which was factually incorrect. Pointed this out to manager and we dealt with it through the proceedings. I have no hesitation in raising these issues.'

- 'We have never had to escalate any issues, but I would feel comfortable doing this because we have a very collaborative environment. We don’t rely on policies but as the business grows, we may need to adapt - but this is not necessary yet.'

Eighty six per cent of respondents had never or rarely reported an ethical concern to someone in their organisation. An analysis of comments from those respondents who had made reports showed that most were resolved promptly:

- 'Always receive a quick and positive response from senior management on ethical or compliance issues.'

- 'I report directly to the executive chair. My input is taken seriously and acted upon. A typical outcome would be a broader discussion with the relevant senior managers and other parties and a conscious decision on how to proceed.'

- 'Generally, the outcome is that the concern is addressed. My organisation has formal governance for addressing certain types of ethical issue.'

Recording risks

Some teams were responsible for maintaining organisational risk registers. However only 10% identified non-compliance with professional regulatory requirements as a risk to the legal team.

For example, a General Counsel in a private sector organisation told us: 'We have a risk register but nothing about regulatory risks. [For example] acting outside competence or delegations’ policy, breaching the code of conduct or escalation because we think this is something people naturally understand.'

Risk registers are not the only way to track and record risks. Other ideas include:

- team meetings

- risk management meetings

- risk committees

- using a compliance system held by another department.

However, you should always consider whether this adequately incorporates legal and ethical risks.

Some leaders felt that having formal compliance policies and procedures to manage risk would be too onerous, however the justification for this was not always clear.

For example, one thought that it was just an expectation that teams would identify risks as part of their role: 'As a growing company it would be incredibly challenging to set specific procedures to follow because there needs to be a comms and training strategy. As we are evolving it would be difficult to set this on a high level and enforce top down. We have development plans and sub strategies where we define the capabilities we want to see, such as identifying risks and soft skills. I feel comfortable that this already makes sense for staff'

Relying on customary practice or understanding means that some in-house teams may not be able to demonstrate compliance with our standards should an ethical risk arise. It also places an over reliance on individuals to manage demanding situations. Political and commercial pressures, or even working relationships can lead to inconsistency in decision making.

Next steps to consider

A good starting point to manage this risk is being satisfied that your employer has appropriate arrangements to help you meet your obligations. Keeping central records helps to provide oversight of issues, track any patterns and trends, and provides a focus to consider ethical risks at an early stage. It could also help to identify any training needs.

Good practice examples

- An in-house team at a property developer created a compliance policy for all in-house solicitors. This included guidance on who is the client within the group, taking instructions and when the Group General Counsel’s (GGC) approval was needed. Guidance was provided on the standards and regulations, file management conflicts, confirming instructions, assessing risks and reporting obligations. This made sure that the GGC was aware of high-risk matters and could review whether instructions could be accepted at the outset.

- A General Counsel at an investment company created a compliance dashboard to capture incidents or issues each quarter to track trends and report to the board. They said that this creates objectivity and the gravitas to drive agenda items forward.

Monitoring risks

Some teams used project trackers and spreadsheets to track matters, but we noted that many in-house solicitors did not have oversight of matters. For example:

- Just a few organisations had clearly defined authority structures in place which made it clear what work needed approval and by who.

- Documents could be reviewed though document share systems, but junior solicitors told us that getting work checked was self-managed.

This helped junior solicitors to feel trusted and have autonomy in their work, however in-house teams should also consider whether they have sufficient oversight.

In most cases, because of the nature of work, personal email accounts and drives were often used for recording documents.

Teams also mentioned that processes were often automated to manage repetitive work activities and resources more efficiently. For example, using technology and template agreements. Some therefore felt that reviews or quality assurance was unnecessary. Project work was also common, and tasks could be diverse and dynamic.

- Junior solicitor: 'It's more organic because it is a transactional and fast-paced environment - so on each project I may just need to ask for help to review a draft.’

- Senior leader: 'Any ethical decisions are typically recorded in an email and so even without central records we think we could track and find it though a file document system.'

However, this places greater reliance on risks being identified by individual solicitors at an early stage. A respondent to our survey also pointed out that as well as using shared systems, individuals need to know how and when work should be shared.

Another respondent commented: 'We can get work reviewed as we use google docs to share and review work which works quite well. You learn more about who to speak to over time, but it was difficult when I first joined. There was not enough direction about the processes and procedures of the organisation to get the right support.'

Keeping central records can help with oversight of matters so that instructions can be risk assessed and the quality of legal services can be checked. It can also provide metrics to manage workflows and demonstrate value.

Just 20% of teams used case management systems. But some were either replacing shared drives with case management systems or considering it as an option.

A senior leader in the public sector said: 'Ideally, I would like a case management system because it provides a good audit trail, and it means we can carry out file reviews. Currently, we manually save emails to keep records of advice. But we recognise that we do not have full visibility of risks unless solicitors are proactively communicating them.'

Failing to have adequate controls may affect the legal function’s ability to identify risks, particularly when managing conflicts and confidentiality. However, some teams commented that it was difficult to find suitable systems for their needs. They would also need to justify the budget required. In-house solicitors need to consider whether their employer’s existing systems and controls adequately manages potential regulatory risks.

Next steps to consider

If an ethical or regulatory concern arose, would you be able to justify your decisions and demonstrate compliance?

Formally identifying who the client is and managing organisational expectations could help alleviate pressures on in-house teams.

Consider a formal policy to support teams and the wider organisation to understand who can instruct the function. It could include:

- ‘Who is my client’, identifying roles and employees who have authority to instruct the legal function. And the circumstances they can or cannot be advised and information about the status of related bodies in the organisation

- Reporting lines to raise issues or seek advice and further support

- A risk assessment, making governance arrangements clear for certain decisions

- A conflict checklist to consider the impact of advice and any confidentiality issues.

Checklists

Have you applied any of the following strategies?

- Maintaining oversight with capacity trackers and case management systems.

- Implementing clear reporting lines and regularly review work.

- Reviewing whether your employer’s current systems and procedures safeguard confidentiality, and adequately covers regulatory, ethical, or legal risks.

- Training staff how to manage and identify conflicts and confidentiality risks.

What your employer needs to know

- We expect all solicitors, to uphold and maintain high professional standards, including balancing the client’s interests with other ethical obligations.

- In-house solicitors should be prepared for challenges by monitoring risks to make sure that organisations are protected and must report serious concerns to us.

- As an employer, you may want to consider whether the legal function has adequate systems and policies in place so that solicitors can meet their obligations. You may wish to discuss how best to do that with the solicitors that you employ.

Where you and your employer can find help

- Read our guidance for unregulated organisations on conflicts and confidentiality

- Read our guidance on your obligations relating to own interest conflicts

- Read our guidance on your obligations relating to conflicts of interest

- The Code of Conduct explains the circumstances you should report serious concerns promptly.

What we expect

We expect solicitors to act in a way which upholds public trust and confidence, and encourages equality, diversity, and inclusion.

Embedding an ethically responsible culture includes establishing an open and supportive environment so that solicitors can meet their professional obligations.

The risk

Most in-house solicitors did not feel they faced unique challenges or pressures in comparison to private practice. Some even said that they thought private practice solicitors faced more ethical pressures.

However, most solicitors in both the private and public sector also told us they often had to navigate a range of political and commercial pressures.

This included pressures from executive stakeholders, elected councillors, senior leaders in public office, consumers, pressure groups and the press or social media. Ethical risks may arise without sufficient support and resources to prioritise ethical choices when under pressure.

Demands from colleagues

Nine out of ten junior in-house solicitors had never felt they needed more support from managers in teams. However, a senior leader acknowledged that junior solicitors may need additional support to manage enquiries from colleagues.

One private sector senior leader said: 'We are challenged if we say no because of the value of contracts. It is difficult to push back particularly if you are junior, so we have a senior member in the team to support them. It's rare but it might be useful to formalise in the future. It helps that I am on the board if things are escalated.'

This could be a wider concern because survey respondents reported that managing demands from colleagues was their most significant cause of pressure. Some felt that this pressure was a result of a lack of understanding about their role and regulatory responsibilities.

However, most survey respondents felt that their regulatory obligations had not been compromised to meet organisational priorities. Additionally, 89% of senior leaders also felt they had enough time and support to manage regulatory obligations.

Workloads

However, a minority (10%) of respondents who felt that their obligations had been compromised, frequently highlighted that time constraints and heavy workloads were the main reason. Typical comments from our survey analysis included:

- 'The organisation's primary business takes priority and I have to deal with regulatory obligations in a very short time or in my own time. Regulatory obligations are seen as my problem and the rest of the business relies on me to deal with them and tell them what to do, with the result that I have to work on them alone.'

- 'It can be difficult to balance the requirements placed on professionals by employers while ensuring that there is sufficient time to carefully consider any regulatory obligations.'

These views are also consistent with findings that 62% of respondents felt that managing workloads was currently their biggest challenge and 16% felt that their current workload was overwhelming.

Comments from respondents include:

- 'With an overwhelming workload you feel you are unable to provide your best work. I therefore question whether this is in line with the Code of Conduct.'

- 'Constraints mean the legal team have to decide between urgent commercial projects with heavy senior executive focus and spending time on managing regulatory risk and compliance programmes. There is insufficient resource to do both.'

A quarter of senior leaders identified that this increase was still mainly because of the Covid-19 pandemic. However, overall workload pressures appeared to be an ongoing issue. This suggests that some in-house solicitors are regularly experiencing personal pressures and high workloads, which not only affects wellbeing but could lead to ethical risks if unmanaged.

Recruitment and budgets

However, just 30% of senior leaders thought their teams would increase in size over the next 12 months to accommodate this and 15% thought they would decrease. Many teams mentioned this was due to difficulties recruiting and retaining talent and issues such as:

- challenges matching salaries in a competitive labour market

- finding people with the right skills

- supporting development

- managing new ways of working.

There was also a concern that flexibility and family friendly policies were no longer attracting staff. Most teams resolved resourcing issues by instructing external firms.

One General Counsel in the private sector said: 'The war on talent is off the charts! How do we retain and attract talent when expectations about remuneration are so high? We can compete on share options, and we bring cultural and social value which helps but we can't get the right people at junior level and hybrid working isn't enough when juniors need to be here to work with senior lawyers and keep up to speed with commercial awareness.'

Without the right resources, the service and quality of work produced by the legal function may not be adequate to manage ethical and regulatory risks. There is also a risk that incorrect advice or advice which is not in the organisation’s best interests may be given. This is a particular concern if more experienced team members who act as supervisors leave.

Most in-house leaders in both the private and public sector told us that legal budgets had stayed the same. But public sector teams were more likely to have experienced cuts. Overall, most teams felt that they could get more budget for recruitment if they needed it with a good business case.

One General Counsel in the public sector said: 'We are expected to still do the same work, but our budget needs to be cut by 10%. I have put forward business cases to keep people though and can bid for additional funding throughout the year.’

Retaining existing staff was also identified as challenging because career and development pathways are not as clearly defined as in private practice. Some legal functions were reflecting on how to retain staff by structuring teams to provide more opportunities for development. Others were developing apprenticeship schemes to try and encourage and engage new socially diverse talent.

Saying no

An important part of the role an in-house solicitor is delivering advice in a clear, business focused way to steer decisions appropriately.

A General Counsel underlined this integral role in organisational decision making when they said: 'We come up with a solution to help the executives make decisions in grey areas rationally by looking at all the evidence. We see the bigger picture and long-term strategic aims to drive the agenda forward. Other teams tend to focus on short-term objectives.'

However, there may be occasions when commercial interests are not aligned with regulatory interests or the public interest, and this will mean advising clients that professional obligations take priority.

Most senior leaders said their influencing skills resolved any issues or conflicts effectively. They provided options and workable solutions for organisations, by explaining risks in a business focused way rather than say 'no'.

For example, a private sector General Counsel said: 'The business doesn't want to do anything illegal - it's about assessing the risk and making sure the execs properly understand what the risk is. Sometimes we take a cautious line but we have a robust process to assess the risks and then put it into the language of the business to set it out in a palatable way.'

There was also a perception that the alternative was being seen as a corporate stumbling block, advice being ignored, or that alternative advice would be sought elsewhere, diminishing their influence. Senior leaders said:

- 'We use our experience and skills to get the business to where it wants to be - "yes, if" rather than "no".'

- 'It's important that the way advice is delivered is "approachable". We don't want to be seen as a "blocker" or a "stopper".'

- '[As General Counsel] it's my role to come up with creative solutions you can't just say no and sit in an ivory tower. It's about understanding your business - and clients with political interests have more opportunity for political leverage. I have to be even-handed and adopt the same approach with both opposition and current administration.'

Pressure to change advice

Providing options helps organisations to make informed decisions from a range of possible outcomes. However, one in four in-house leaders also reported that they had experienced pressure to change their advice to support commercial interests.

This pressure may be exacerbated if the wider business does not fully understand an in-house solicitors' regulatory duties. Our survey respondents said:

- 'It can be difficult for the organisation to understand what my obligations are and what I can and can't do. I frequently have to educate/remind people about my regulatory obligations and why we must comply with them generally. That regulatory compliance is standard business practice which doesn't make us uncommercial.'

- 'I felt that my ability to provide independent advice was being compromised as a result of the priorities by certain individuals within my organisation.'

Furthermore, 5% of respondents had experienced pressure to suppress or ignore information which could conflict with their regulatory obligations. Their survey answers raised serious concerns, for example:

- 'Asked to make up a situation that was not correct. We didn't do it in the end.'

- 'Strategic and policy decisions were frequently made by the executive management team to prevent disclosures.'

- 'The organisation I worked for was engaged in practices I considered were likely to result in breaches of their legal duties. It required me as a solicitor to report as an officer of the court. I raised concerns with the senior leadership and as a result had to leave the organisation.'

- 'Breaching disclosure obligations. Hiding data. Using illegally obtained information for litigation.'

- 'Requested to overlook severance payments to outgoing staff which fell outside delegated authority of awarding staff. Asked to overlook unlawful procurement.'

This highlights that balancing commercial imperatives, client needs, and ethical obligations can be extremely challenging when working in-house. Inevitably, the stakes are particularly high for employees when saying no and we saw evidence that it can even mean making the difficult decision to leave a role.

Overall, many in-house leaders discussed making decisions collectively. And almost all (98%) respondents said they would feel comfortable saying 'no' if asked to advise on a course of action that was unethical.

This view was also echoed by senior leaders during visits and most felt that ethical pressures were not a significant concern. For example:

- 'I've never really felt any ethical pressures or compliance concerns. I know what my role is and what I need to maintain. I will stick up for any issues and left my last organisation when I had to. Why would other solicitors not do this?'

- 'My job is to keep my colleagues out of prison - you have to think there but for the grace of God - and of course, no-one wants that. It's not like you have to agree with the boss. My responsibility is to the court. I am here to help and protect you but I also have to wear different hats sometimes. In my role sometimes you are enabling people to get on and other times you have to advise them of the consequences should they do something. But usually it's a round table discussion.'

However, a risk remains that these pressures could lead to ignoring unethical activities or changing unwanted advice to retain jobs, credibility and working relationships.

Several senior leaders acknowledged that their advice may be ignored. This is because the organisation wanted to pursue a different course for commercial reasons, or because they had a different risk appetite.

Notably, survey respondents who felt that the legal function was not valued frequently mentioned that their advice was ignored, misunderstood, or challenged. For example:

- 'Simply put, there is no appreciation of the work that is done to generate income and protect the reputation of the organisation.'

- 'Legal advice is often challenged at all levels without understanding of the law or basis upon which advice is given. This is largely because they have already committed to a course of action and want legal advice to rubber stamp an approach.'

A different view was provided by a General Counsel in a private sector organisation who expressed concern that their role as ethical gatekeepers was being overplayed and unhelpful in practice.

'We are not the police, we are like helpful aunts and uncles that can guide and advise. It's better to work with people in the business, rather than appear critical as otherwise they won't come to us and potentially leads to more risk. I think we have the balance right here - people come to us which means we are more likely as an organisation to do the right thing rather than ignorantly get it wrong.'

Next steps to consider

Being approachable and accessible is important in a commercial environment. However, it is also important that employers are aware of the circumstances where a solicitor’s regulatory obligations would take precedence over the organisation’s interests.

In-house teams may want to consider how they can manage organisational expectations to support solicitors who may need to say no in certain circumstances.

Professional isolation

We also saw that one in four survey respondents and half of General Counsel felt that professional isolation was their biggest challenge working in-house.

Managing pressures such as demands from colleagues and senior corporate roles were common concerns from our review that could lead to feelings of isolation.

One General Counsel exemplified this when they said: 'We are often a lone voice when trying to manage risk appropriately.' For some, being a sole senior female leader added to this isolation.

A General Counsel in a private sector organisation said: 'I might often have a different perspective in the room and having to voice this can be tiring. I feel clear that having a divergent view is part of the role and mandate. You see things from a different risk perspective and have a different set of competencies. As General Counsel - and also as the only woman in the room.'

Many in-house leaders discussed the importance of building personal resilience, and some had personal coaches to provide support and space to discuss concerns. Some discussed seeking support by developing relationships with other non-lawyer senior leaders, particularly chief financial officers.

A General Counsel in a private sector organisation commented:' Covid was really challenging financially for our company and also in my professional career as all eyes were on me. I found that really hard, but I also discovered that I have huge amounts of resilience. I have a coach who knows the business and my team is very supportive. I also attend networks to meet other senior women.'

They also explained that they felt it was important to educate the business about the role of the legal function, for example about their capacity and how instructions are received. They delivered training to make sure they worked in partnership with different teams and senior leaders across the organisation.

Working in law can be extremely pressurised, stressful, and even lonely, particularly in senior in-house positions, or in small in-house functions. These pressures if unmanaged, could not only lead to wellbeing concerns but also potentially to regulatory risks.

Most senior leaders described having high levels of resilience. However creating networks and building supportive working partnerships are a helpful way for senior leaders to discuss ideas, concerns, and workplace challenges.

Demonstrating value

Almost all respondents (95%) said that the legal function was valued in their organisation. Many in-house solicitors saw themselves as trusted advisers who add value with a blend of commercial, operational, and legal knowledge.

Most in-house leaders also felt strongly that they had a part to play in shaping the corporate agenda. Therefore, it was important to clearly demonstrate wider commercial value in facilitating business objectives.

However, some in-house solicitors acknowledged that this could be difficult because advice or even managing legal risks wasn't always visible or easily measurable. Comments include:

- 'It's difficult to define our value to the business. Is it a proportion of commercial spend to legal spend - the amount we save from not doing it externally? I'm going to ask the senior management how many hours we spend with them.'

- 'Our general legal advice adds value because we understand the risks and we can add a rigour to find solutions. But the business often doesn't see it because issues are often mitigated before it happens.'

Not only does this place additional pressure on senior leaders to deliver more but it could also have a direct impact on investment in the legal function, putting pressure on resources.

More than a third (35%) of senior leaders found it difficult to secure more budget investment in the team and were considering how they could demonstrate their value better to employers. Typical comments include:

- 'It is challenging - 85% of our budget is personnel costs and seen as an overhead. I need to create a good business case in the language of the business with KPIs. Numbers to make it meaningful to sell the cost in the right way.'

- 'We are thinking about being more sophisticated about how we present our case with metrics - in house teams are not necessarily good at that.'

This is important as one in-house team highlighted that tight resources and heavy workloads were impacting on their ability to add greater value to organisations:

A General Counsel in the public sector said: 'We are still heavily constrained and could add more value if we were not so stretched and had such high workloads. We would like to do more holistic things for training the business to manage risk but don't have the time. It feels like a failure.'

For many it was crucial to be involved in projects and discussions at an early stage to add real value. Another General Counsel in the private sector commented: 'We are valued as a knowledge bank and part of the corporate memory in terms of compliance. If it gets us a seat at the table that's ok - as long as we have the respect at the top. At the bottom we have to educate more about our role.'

An in-house team explained that they were proactively delivering training for colleagues in other departments to help them understand how to instruct the legal function. This also helped to demonstrate value, promote the team more widely across the organisation and manage workflows.

Next steps to consider

One way to articulate value and help the whole team feel they have influence is to identify your purpose, goals, vision, and values. Ask the organisation and your team for their ideas and feedback and identify where the team add value or could do more.

Follow up with further engagement, communications, and training to improve understanding about receiving instructions, roles, responsibilities, obligations, and standards of service.

Checklists

- Teams are supported with regular one to one’s, supervision, and team meetings to discuss challenges, concerns, and questions.

- Workloads are not so wholly unreasonable it affects standards of service or competence.

- Time is set aside to reinforce and remind colleagues about their regulatory duties.

- Metrics and service level frameworks demonstrate value and manage workflows.

What your employer needs to know

In-house solicitors have obligations that extend beyond the provision of legal service. They also have to adhere to ethical principles and standards of behaviour that uphold and maintain the trust and confidence the public places in them.

Where you and your employer can get help

- Read our guidance for unregulated organisations that employ solicitors.

- If solicitors need advice about obligations, contact our Professional ethics helpline.

What we expect

In-house solicitors must provide a proper standard of service to their client and integral to this is meeting the competences set out in the Competence Statement. Like all solicitors, those in-house must reflect on their practice and undertake regular learning and development.

The risk

In-house solicitors need time and support to maintain their continuing competence and regulatory obligations. This includes access to relevant legal training and opportunities to reflect on areas for professional and personal development. A failure to reflect on learning needs and undertake suitable learning and development could affect their ability to provide a high standard of service.

Demonstrating learning needs are being addressed

Having an opportunity to reflect on the quality of your practice helps to identify learning needs and plan what you need to do to address them. We asked senior leaders and junior in-house solicitors to provide a copy of their learning and development plans in advance of our visits. Most solicitors showed us a development plan provided by their organisation.

In most cases, this showed a list of training courses with corporate development objectives. In most cases it was not clear what development needs had been identified and whether the steps taken actually addressed those needs.

Just one junior solicitor chose to use our development plan template. This satisfactorily recorded that they had reflected on their practice and identified and addressed learning needs. Interestingly, their General Counsel, used their organisation’s generic development plan which listed objectives linked to corporate strategies.

Next steps to consider

It is not mandatory to use the template or have a training record, however keeping records can help you to reflect on learning needs. Using one of our templates is a straightforward way to make sure you are recording the right information and can demonstrate competence requirements are being met.

Learning and development activities and ethics

Learning and development should include regulatory or ethical considerations as part of continuing competence and supervision should provide an opportunity to discuss these needs and plan training activities.

We reviewed the learning and development activities that had been undertaken by senior in-house leaders and junior solicitors in the last 12 months by referencing the competence statement.

Overall, there was an even proportion of commercial and legal training over 12 months. However, we noted that of recorded learning activities for junior and senior solicitors over the same period:

- 70-80% involved technical legal practice

- 35% overall involved ethics, professionalism, and judgment

- 25% of junior solicitors had not received any ethical training

This could mean that these solicitors do not have enough support to recognise ethical issues, a critical way to help organisations meet high standards. Additionally, just 15% of senior in-house solicitors had reviewed their team’s learning and development policies within the last 12 months to update learning activities.

When using their employer's learning and development materials in-house solicitors must make sure that any objectives include reflecting and addressing learning and development needs.

One in-house solicitor commented: 'We didn't have development plans until last week, but they were apparently introduced a year ago. The training balance is about a 60 / 40 split in favour of the business and commercial training. We use a HR resource but not much is legally related.'

However, although resources for learning and development varied in organisations, most in-house teams had access to a wide range of legal and non-legal training. Commercial training, leadership skills, mentoring and networks were an important aspect of learning and development for senior leaders, as was learning from practice.

A General Counsel in the private sector commented: 'When I started here circa 13 years ago, I wanted to be a better lawyer. Over time I realised that I needed to learn other skills such as management skills and leadership. The company sent me on mandatory three day course to get them and there is always a focus on non-legal training and skills.'

Almost all senior leaders (90%) felt that their employer actively supported them to maintain their continuing competence. This most often related to being able to attend training and having a dedicated training budget. Those that disagreed mentioned having to direct and generate their own training.

One General Counsel in the private sector said: 'They cut our training budget by over half - but it's difficult to get our employer to know how important it is. We have to supplement with free training from our panel firm and webinars, but this isn't as readily available. If our employer knew how important this was so we can spot risks, they would understand we need legal training.'

Most training was delivered by external law firms or barristers or received in daily or weekly emails from law firms and online legal databases. Some in-house solicitors indicated that budgets limited access to appropriate learning resources. For example, public sector General Counsel said: 'We will do what is the most cost effective which is mostly what we can obtain free from firms and Counsel. We just have a general budget that I dip into if I really need something like a coaching course.'

Junior in-house solicitors also commented that self-managing learning and development activities and relying on free training had limitations:

- 'I've missed law firm training on a wide range of legal developments, corporate training, training in teams and at associate meetings. There needs to be more centralised co-ordinated training available in-house like in private practice with someone responsible for it. I think other teams might feel the same. It would be good if resources are pulled together by law firms to make their training available for in-house organisations.'

- 'In-house, you are reliant on law firms coming in to train you as we have no knowledge in the management team. Training is all self-driven. I select it and sign up to it, but no-one has ever asked about my development or what I need to focus on.'

In-house solicitors should remain mindful of the need to take responsibility for reflecting on specific learning and development needs, particularly in relation to regulatory obligations.

Time to reflect and undertake learning

Meeting our competency requirements is an important part of being able to deliver a proper standard of service to your client. Overall, most survey respondents (90%) felt that they had enough time to maintain their competence.

Junior in-house solicitors told us that their learning and development needs were usually identified and addressed during supervision and in one to ones. Training was ranked by survey respondents as one of the least likely ways to discuss regulatory obligations. However, many also reported that heavy workloads, a lack of training and support and multi-faceted roles made it difficult to find appropriate learning opportunities.

One commented: 'With workloads it is challenging to review continuing professional development especially in the general role that I hold. The work type is broad and developing expertise in all areas would be nearly impossible. Otherwise, the organisation supports regulatory obligations.'

This was also reflected in our discussions with senior leaders who said that their workloads had increased in the past 12 months, and some indicated that teams needed more support and resources to grow and develop.

A General Counsel in the private sector said: 'At the moment it's difficult to manage and we don't have any time for reflection. It's hand to mouth rather than having the space. The only time I have to consider regulatory obligations is on holiday.'

Regular supervision and one to ones provide an opportunity to discuss personal development, skills and learning needs. However, one in four junior in-house solicitors felt that they did not have enough support to maintain their competence. And there appeared to be little oversight of learning needs.

Line managers must make sure that any individuals they supervise are competent to carry out their role. And keep their professional knowledge, skills and understanding of legal, ethical, and regulatory obligations up to date. This means they are responsible for all members of the legal team they supervise.

Supervision and one to ones

Most survey respondents directly reported to another member of the legal team, but senior leaders tended to report into a non-legally qualified person such as the CEO. Most survey respondents identified one to ones and team meetings as a place they could discuss their regulatory obligations and competence.

Senior leaders also used one to ones to monitor capacity and delegate work if necessary. This suggests that it is important that opportunities for discussion take place regularly. However, in reality, in the legal teams we visited, they were often provided on an ad-hoc basis.

Most junior solicitors told us that they self-directed their work and approached their line manager for supervision as and when it was needed. For many in-house solicitors, this provided a sense of autonomy and a feeling of being trusted in a mature environment. Most also felt comfortable that support was readily available if needed.

However, some junior solicitors reflected that in practice this meant a lack of regular support which may make it difficult for individuals to identify when tasks are beyond their competence or when they need to ask for help.

An in-house solicitor said: ‘There isn't really structured supervision or one to ones although there are meetings allocated in the calendar. But the onus is on you to reach out to line managers each week and say you want to use the time and most people don't.'