Workplace Culture Thematic Review

8 February 2022

Executive summary

Workplace culture defines the character of a working environment and is built by those who work there. It is established by the behaviours, attitudes, and values of leaders and employees and is supported by its systems, controls, and procedures.

Perhaps more than at any other time, the impact of changes to our working environment has placed culture firmly under the spotlight. A poor culture not only affects personal wellbeing but also ethical behaviour, competence and ultimately the standard of service received by clients.

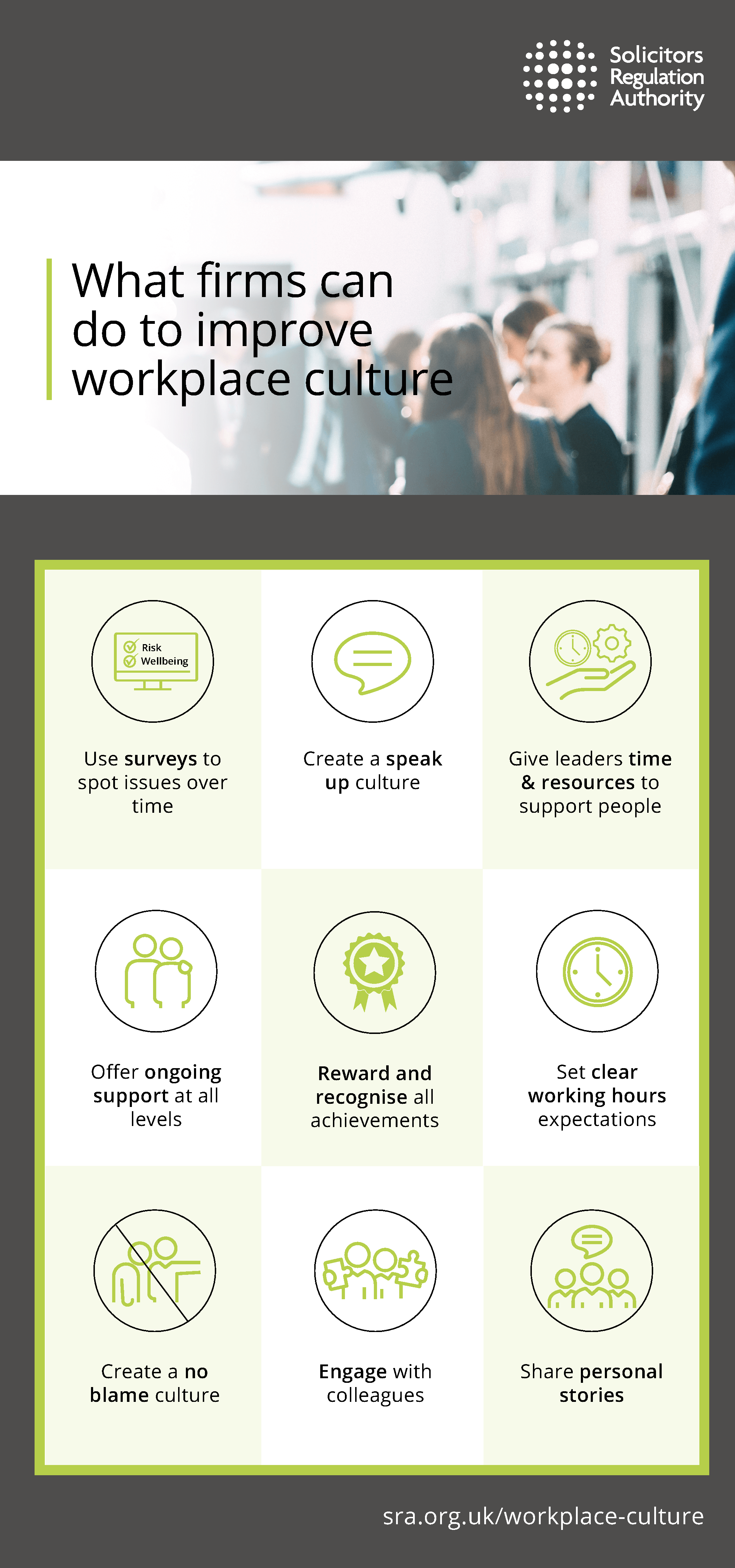

In contrast, positive workplace cultures can be characterised by the following qualities:

- inclusivity and core values such as respect that are lived by everyone

- authentic leaders that lead by example and model positive behaviours

- a no blame culture and an open, speak up environment

- reward and recognition for all aspects of work and achievements

- employers regularly engage with employees and seek their feedback

- supportive, collaborative teams and opportunities for social connection.

There are both challenges and opportunities for firms who want to improve their workplace culture. This report draws on the experiences of employees and firms to examine the interrelationship between meeting high standards in working practices, supporting wellbeing, and minimising risks.

What we did

Creating a positive culture is crucial for the effective operation of law firms. Our thematic review looked at how firms can create such a workplace, where employees feel supported, risks are managed, and clients are protected.

We did this by examining how firms support people in the following areas:

- managing client pressures

- management of workloads and allocation of work

- reporting mistakes and near misses

- supervision, learning and development

- measuring performance and reward and recognition

- recognising the signs of poor mental health and helping people to speak out.

We also explored the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic on culture in firms and how this may influence working practices in the future.

We gathered views from organisations, firms and individuals in the legal sector including:

- Elizabeth Rimmer, Chief Executive, LawCare

- Professor Richard Collier, University of Newcastle a writer and researcher on law and wellbeing and contributor to LawCare's 'Life in the Law' study

- Manda Banerji, immediate past Chair of the Junior Lawyers Division (JLD)

- Katie Heiden, Lockton Solicitors

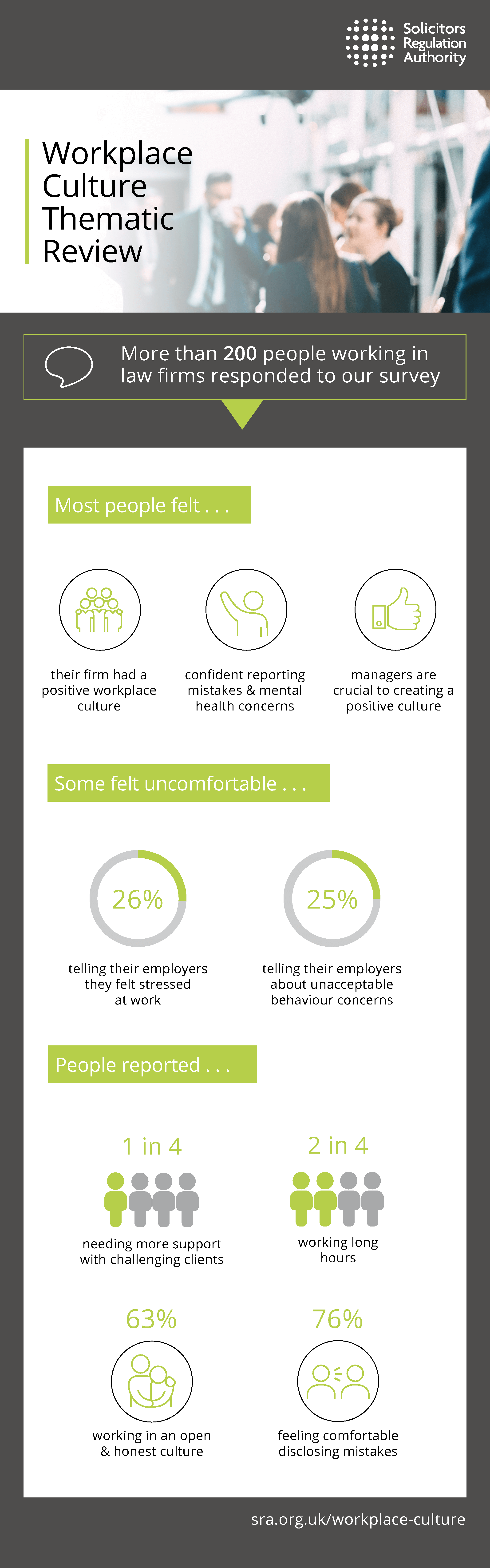

- more than 200 solicitors and people working in law firms who responded to an anonymous survey (respondents)

- follow up interviews with respondents willing to discuss their answers in more detail

- in depth interviews with 12 small, medium and large firms striving to prioritise wellbeing, and fee earners.

What we found

Most respondents felt that their firm had a positive workplace culture with slightly more agreeing that their immediate team or department were positive.

This was supported by evidence that most respondents also felt confident reporting mistakes and mental health concerns to employers. Overall, supportive senior leaders and line managers played a crucial role in creating this culture at firms.

Some common themes from our review were:

- the importance of engaging and involving employees in decisions about their culture

- creating a psychologically safe environment to speak up about worries and concerns

- the value employees placed on support from line managers and colleagues in teams

- the benefits and challenges of remote working and its effect on trust

- balancing wellbeing with commercial requirements

- a disconnect between the actions of senior leaders and the culture they promoted.

A quarter of respondents felt their firm didn’t have a positive culture and highlighted concerns such as:

- long working hours

- pressures from clients and workloads

- targets that ignored other achievements

- worries around reporting mental health issues and bullying behaviour.

Factors that can affect a working culture are interrelated and ingrained in working practices. However, firms who were trying to create a positive culture focused on rebalancing commercial interests with the wellbeing of employees. This was underpinned by regular engagement with employees, and feedback to build trust and make policies meaningful.

Firms told us that prioritising employee wellbeing also benefited their bottom line in the following ways:

- Lower turnover of staff reduces recruitment costs.

- It helps to attract new talent and small businesses to grow.

- Firms are protected from claims if employees come forward and admit mistakes.

- Professional indemnity renewal is easier because it increasingly asks questions about culture and happier staff means lower numbers of claims.

- Happy, productive staff create a better client experience, and this brings in work.

- Clients are increasingly interested in culture and focusing on this differentiates firms from others in the market.

As one firm said, focusing on wellbeing creates a ‘virtuous circle’ attracting and retaining the best employees. These employees are then more productive, motivated, and engaged to work as a team, which in turn benefits clients and their business.

What your firm can do next

We want to support firms to create healthy workplaces and supportive cultures so that they can deliver good outcomes for clients. Within each topic below, you will find helpful information and resources to support your firm to develop a clear direction and help meet your workplace goals.

Resources include:

- Good practice examples from solicitors, law firms and their employees.

- Checklists to help inform your firm's approach and wellbeing strategies.

- Actions you can use as part of your planning process to develop specific tasks.

- Further help and information available through our guidance and other organisations.

- Videos featuring partners at law firms, offering insight into specific areas.

Managing workplace challenges

Open allWe expect firms to create and maintain the right culture and environment for the delivery of competent and ethical legal services to clients with effective systems, supervision arrangements, processes and controls in place.

This includes taking steps to run businesses in a way that supports wellbeing by minimising the risk of working practices and workplace behaviours leading to poor mental health. A failure to put in place systems that protect employees may lead to an increased risk of breaching our regulatory requirements.

Lawyers need good mental health to deliver what can be a challenging role in clients’ best interests. Being able to speak out about mental health difficulties and supporting employees at an early stage could prevent concerns and issues escalating. It can also support firms to minimise risks such as reputational damage.

If employees are not adequately supported to manage mistakes or to manage client demands, they may be at risk of behaving unethically. If mistakes are made, you should be open and honest with clients, if they are affected, and explain promptly what happened and any consequences. We will always look at the context of misconduct and try to understand any wider mitigating or aggravating factors that may have contributed towards any issues.

We also expect you to report any matters you reasonably believe could amount to a ‘serious breach’ of standards and requirements. Our Enforcement Strategy explains more about your obligations to report concerns to us and other legal regulators.

Firms should encourage equality of opportunity, equal treatment, and respect for diversity so that employees are treated fairly at work. Prevent unfair or inappropriate treatment by doing everything you reasonably can to protect employees from bullying, harassment, discrimination, and victimisation.

Working in law can often be challenging and pressurised but when symptoms of stress are unmanaged, it can become overwhelming and may lead to crisis or 'burnout'. One study reported that 66% of solicitors are currently experiencing high levels of stress.

Known contributors to poor mental health in the workplace include:

- long hours

- unmanageable workloads

- unrealistic expectations and deadlines

- poor communication and poor support.

Working with some clients in particular sectors, such as in pressurised commercial environments, family law and criminal proceedings, or with challenging, vulnerable, or traumatised clients can also be personally and professionally demanding.

If employees do not feel able to disclose mental health difficulties, or concerns are not spotted at an early stage, this could lead to issues escalating out of control.

Our survey indicates that most people feel safe disclosing mental health issues at work and 70% said they could tell their employer they felt stressed at work. This may be due to improvements in communications, support, and awareness.

For example, most firms we met facilitated open dialogue by providing access to a service that provides psychological support or counselling. A third of firms provided training for peer support arrangements including Mental Health First Aiders (MHFAs) or mental health ambassadors/ champions. Fifty-eight per cent of firms trained managers to identify early signs of stress which could mean they are better prepared to intervene and proactively support employees.

Most firms also implemented wellbeing checks during the Covid-19 pandemic lockdowns. However, this this type of activity must be followed by positive action to feel authentic as highlighted by one respondent. They felt confident reporting they felt stressed but said 'Managers check in but there's no action taken and no accountability or responsibility on management.'

Day-to-day team support

When we asked employees at firms what helped them to feel psychologically and emotionally supported, it was the day-to-day experience of being supported in a team that appeared to matter most.

Many mentioned shared activities such as calls to check wellbeing, friendly colleagues, peer support, social activities, catch ups with managers and approachable partners who supported flexible working. A junior solicitor said: 'The culture is good. I speak to colleagues and can pick up the phone to someone my level or just below and senior leaders on an informal level. On a formal level mental health champions are available and trained.'

This suggests that people are happiest when they feel supported by colleagues and feel able to discuss issues and concerns with others. Making space for sensitive discussions is an additional challenge for remote and hybrid working teams but maintaining peer support, and informal catch ups can encourage open dialogue. Another junior solicitor noted that 'it used to feel stressful to bother the partners. It's nice to touch base with line managers to get reassurance first if you feel stressed.'

Supportive line managers

Some respondents also highlighted positive outcomes when they disclosed concerns to supportive line managers:

- Solicitor, six-plus years' Post Qualifying Experience (PQE): 'I suffer from anxiety and depression. I informed those around me, and they have been unfailingly supportive. I fell apart in front of the managing partner and they were understanding, removed the file that was causing unnecessary stress and discussed ways further support could be provided. As a result, I have been able to pull through and am now significantly more productive. Understanding and support is so important in this area.'

- Solicitor, six-plus years' PQE: 'I was struggling with work and personal issues and had no worries about telling my supervisor who supported me taking time off. I had a month off, which all senior managers supported, and made a huge difference to my mental health. When I returned, I was much more productive and focused.

Admitting concerns

However, a smaller number of respondents said that they would not be comfortable admitting they were stressed. They highlighted concerns about the negative repercussions of disclosure, or that it would be perceived as a sign of weakness. For example:

- Solicitor, less than five years' PQE: 'Because they might think I don't have what it takes, and I am just not capable or weak.'

- Solicitor, six-plus years' PQE: 'It would be seen as a weakness / vulnerability and there is no safe place for that in this workplace.'

- Solicitor, six-plus years' PQE: 'Iwould be likely to be ridiculed by the senior partner and work would be removed from me or (I would) not be trusted with further work.'

These views might arise if high levels of stress are normalised as simply being an accepted part of working in a law firm. Some respondents also worried their concerns would not be taken seriously or would be ignored.

- Solicitor, less than 5 years' PQE: 'The culture is one where you are encouraged to take as much on as possible.'

- Trainee solicitor: 'I have repeatedly told my manager of worrying stress levels and unachievable targets and no action has been taken.'

Good practice

Strategies and policies

A small employment firm focused on the wellbeing and mental health of their employees as part of their overall strategy. They promote wellbeing from induction and this forms part of their regular one to ones with employees to keep communications open about behaviour and expectations. Different managers with a variety of expertise conduct sessions and employees are encouraged to give 360-degree feedback and be honest with each other. They also trained all employees to be MHFAs.

Supporting wellbeing with policies and events can also help to minimise stigma and reassures people that their concerns will be treated fairly and positively. Half of firms had introduced new wellbeing policies and initiatives because they were concerned about the effects of lockdown on the wellbeing of their employees.

Firms also said that signing up to initiatives, such as the Mindful Business Charter, provided useful learning opportunities and sent the right signal to employees and clients about their commitment to wellbeing.

Personal stories from senior leaders

Some firms told us that senior leaders used personal stories about their own mental health to open dialogue, provide reassurance and challenge stigma. For example, a firm launched a mental health programme and senior people disclosed their mental health challenges in a publication and a seminar.

They said this sent a powerful message that no one is immune to mental ill health. In one seminar, a partner discussed their experience of having a breakdown. They wanted people to know there is nothing to be ashamed of and it's okay to show vulnerability, to underline that mental ill health is an illness not a weakness.

Good controls and monitoring practices

Having good controls in place to monitor workplace risks like stress can provide the tools to help people thrive. Many firms used pulse surveys (brief surveys which regularly ask the same questions) to collect regular feedback about how people are feeling. This helps to score levels of happiness, track trends over time and identify risks. A firm commented that this provides reassurance that they are doing the right thing or how to do better next time.

Examples of good systems and controls implemented by firms include:

- a small employment law firm conduct mental health risk assessments twice a year to monitor and manage stress. They also use an app to capture information and produce a report on a quarterly basis about how people are feeling

- trackers to report on employees' physical and mental health. Firms review these regularly to look for trends, occupational health issues or themes for learning and this will influence their wellbeing strategy

- board level governance structures to provide oversight and develop strategies

- a wellbeing steering group to proactively identify concerns. They meet quarterly to assess sickness absence, attrition, and access to their employment assistance programme

- a wellbeing task force to co-ordinate feedback to develop a new firm charter and improve wellbeing in teams.

Good practice example from a firm: Small firm prioritising wellbeing

A small firm explained how they prioritised wellbeing for their employees through dedicated policies and working practices:

'We hire a counsellor for the whole team to access psychological support every month. It's reassuring for employees to see that senior colleagues also feel challenged and overwhelmed sometimes. We use sessions to discuss cases and any difficulties people have, to manage the emotional impact of work and to stop any unhealthy behaviours. It provides an opportunity for open dialogue in a safe space to support employees.

'On one occasion, a junior member of staff admitted making a mistake and discussed their worries about the consequences. I was able to reassure them that I had also made a similar mistake and found a straightforward solution. In terms of cost, it was a relatively small amount to monitor a risk to my people and business and it's good to know that staff have someone to discuss emotional issues with before burnout happens.

'We underpin this support with dedicated policies, procedures and working practices that protect psychological wellbeing. We do not have chargeable hours targets, taking on new clients is collectively agreed, and workloads are managed by identifying individual needs.

'For us, everything needs to be meaningful and achievable - and that includes caseloads, business targets and wellbeing. Some firms respond to burnout with a 24-hour GP, but we don't want our staff to get to that point in the first place. We want to create a working environment that doesn't create challenges that need to be overcome.'

Checklist

Does your firm apply any of the following strategies?

- Challenge stigma and raises awareness through initiatives such as wellbeing days.

- Train managers to proactively spot the signs of stress or burnout.

- Invite colleagues to train as MHFAs to support wellbeing.

- Regular one to ones to facilitate discussions about health and wellbeing.

- Use risk assessments to monitor risks including the work/clients you deal with.

- Promote psychological safety at work so that people can be open about worries.

- Lead by example and share personal stories to reassure colleagues about disclosing concerns.

Action: Create a wellbeing strategy

- Invite employees to help design your wellbeing strategy and shape their culture. You could include other firms or even clients in the process.

- Include a set of objectives, actions, core values or expectations.

- Consider how it will be delivered, communicated, and embedded most effectively.

- Remember it's a living document - seek regular feedback and be open to change.

What firms said

'We have learned we need to push more into the front line of communicating our culture especially what our intentions are. For example, how we can be more resilient and honest about the low points as well as the highs and telegraph where we are going.'

Further help

Balancing competing demands between commercial interests and the wellbeing of employees is a key challenge for firms and employees. Clients in some sectors may be particularly demanding of time and resources or expect high levels of access and personal flexibility from partners and employees. With more virtual meetings, this can mean working under significant pressure, as well as longer hours.

A good work-life balance

We asked fee earners at firms what aspect of their work culture they valued the most and they most frequently ranked having a good work-life balance the highest. We also asked senior leaders what they thought their employees valued the most and they also said work-life balance.

Senior leaders know that their people want to have greater balance in their working lives, however only 17% of survey respondents reported working within their contractual hours and two out of four respondents worked significantly more than their contracted working hours.

Additionally, only 30% of respondents said their firms did not expect emails and calls to be answered outside office hours. These pressures may culminate in some employees struggling to balance work and personal lives to such an extent, that it harms their health and wellbeing.

Senior leaders' behaviour

The behaviour of senior leaders was often viewed as a key indicator of the reality of a firm’s expectations around working hours and was frequently highlighted as an area that respondents would like to change about their culture. For example, one non-fee earner said that if they could change their culture, it would be that ‘the leadership set a better example about switching off and being realistic with client expectations’.

Leaders play a crucial role when setting the cultural norms for firms. Their actions establish how culture is viewed by employees and what potential career development looks like. As another solicitor, six-plus years’ PQE, said: ‘the presumption of long hours is a contributor to why certain groups do not progress within the career structure. As a woman, I have turned down partnership positions because all I could see was ...constant work. No life at all. As an employee, I have slightly more protection and slightly more non-work time.’

Supportive managers

One in four employees we spoke to said that they would like more support from their line managers when dealing with challenging clients, as this had an impact on their working hours. A trainee solicitor said if they could change their culture, it would be one ‘where it is not questioned, if you say you cannot work during an evening or on a weekend, and time off means truly 'time off' rather than being on call.’

A small firm stressed the importance of leaders ‘walking the walk’: ‘It’s important for senior members to be trained to support our policies. It was easy as partners to get into the habit of answering emails on holiday and this didn’t seem unusual. However, our employees told us that this made them feel pressurised to answer emails out of hours too - even though our policies stated that this was not expected. Policies are good but they must be meaningful.’

Flexible working

Many firms promoted flexible working patterns but some fee earners still highlighted issues around meeting client demands and an expectation of being available, even at weekends. Firms who are striving to make changes that promote greater flexibility for employees must ensure that their polices are meaningful by regularly seeking feedback.

Remote working is increasingly being offered by firms as a flexible working option, but this is not a panacea for achieving a work-life balance. Technology has made remote working possible but may mean that more time is spent online. Some firms noticed that employees took less time off for sickness when working remotely and worked longer hours.

Respondents also reported that expectations around working hours had worsened with remote working and it was more difficult to switch off. One trainee solicitor commented: ‘Since the pandemic and work from home started there is the expectation that everyone should be available to answer calls and work 24/7’.

Good practice

Promote a supportive and collaborative work environment

There will be times when people must work late or additional hours to meet client needs, however try to balance client need and the needs of employees as far as possible. Firms we met, introduced regular communications to encourage employees to take regular breaks and holidays. One firm shared photos of senior leaders having time away from their desks.

A solicitor, less than five years’ PQE, highlighted that their firm offers time off in lieu if they work additional hours and they can have time for personal activities such as appointments. They said: ‘there is never any discussion about the hours I’ve done because it only matters what has been achieved. Appraisals cover how the team are doing to maintain targets.’

A small firm managed working hours by restricting emails: ‘We manage burnout by making sure people don't work late or at weekends. We do not have emails on phones, and they are set to switch off automatically. We are not paramedics; things will still be ok in the morning.’

Set working hours expectations

Improving communication with clients and setting out joint expectations around working hours can help everyone to understand the culture you and your colleagues want. This could be a business code that is shared between firms and clients, or clear and consistent messages in communications or email footers about working hours from senior managers.

Partners played a key role when managing client expectations on employees’ behalf by taking responsibility for issues at busy times. As one fee earner told us, it is not easy to push back successfully against a client without the support of a partner. Most fee earners said they had to be proactive about finding this support but when they did, partners were supportive, and this was viewed positively.

Both firms and fee earners recognised that while senior leaders talked about the importance of working within core hours, this didn’t always reflect their own working patterns and as a result risked feeling inauthentic.

A partner at a large firm highlighted that wellbeing initiatives can fall flat if they are not actively role modelled by leaders. They said: ‘I’ve underestimated how much junior people are influenced by senior leaders. If you say they don’t have to work late and weekends, but you are doing it - it doesn't ring true, and they will challenge it. Initially I argued that this was my role as a partner- but they said you're putting me off being a partner. It’s just not good enough to say do as I say, you must think about how it looks from their point of view in terms of their career.’

Flexible working patterns

Flexible working means different things to different people. Some firms used surveys to ask for people’s views on working arrangements and to develop a strategy for future working. Having an open approach to work patterns can also help to manage any perceptions of unfairness when balancing work allocation and workloads.

Empowering people to have more control over working patterns increases levels of autonomy which is known to have positive effects on wellbeing and improves job satisfaction. We saw evidence that firms are trying to offer greater flexibility to employees.

For example, a firm introduced a new agile way of working where employees are trusted to choose their own hours if this meets the needs of the team, the business, and clients.

The value flexibility provides employees was highlighted by survey respondents:

- Solicitor, less than five years’ PQE said: ‘My firm prides itself on its flexible culture and doing things differently – when you join, they say we trust you to work and manage your workload. There are no fixed hours. We also have unlimited holidays, and they measure our success based on clients’ satisfaction.’

- Solicitor, less than five years’ PQE said: ‘My firm actively encourages flexible working; working from home has been the norm and staff have free choice about how they want to work in the future. Flexibility is actively encouraged by board members who explain how they have been working flexibly. This has really empowered everyone to decide how they work best and how best to meet clients' needs.’

Other examples of good practice at firms included:

- a partner noting their working hours on email footers to send a signal to more junior employees and clients that they are not continuously online

- encouraging employees to take time off, for example starting later or leaving earlier, if they had been dealing with a particularly challenging case or client.

Good practice example from a firm: Managing client expectations

A small firm highlighted that it's also important for clients to understand their expectations about protecting the wellbeing of employees. They said:

‘We protect employees from long working hours by managing client expectations at an early stage. We send a communication guide to all new clients that sets out their normal working hours and stipulates that staff cannot be contacted while on leave.

Some clients will push and ask if staff are going to be available when they need them, and this is a very difficult conversation to have. It is equally hard to maintain those boundaries when trying to be competitive. If we say we’re not available at all hours, you know another firm will speak to a client at 20.00 on a Saturday and so clients may say they’ll take their business elsewhere. But we pride ourselves on the quality of work we do and so sometimes you need to turn down work.’

Checklist

Does your firm apply any of the following strategies?

Manage expectations about access to fee earners and partners with clear communications to colleagues and clients.

- You are proactive about providing support to manage client demands.

- Senior leaders lead by example when taking leave and working within core hours.

- Remind employees to take regular rest breaks and annual leave.

- Show you value contributions if occasional out of hours work is required.

- Support employees to find the right work-life balance for their role and needs.

Action: Set the tone from the top

- Set the tone for your culture by modelling positive healthy working patterns and share your work-life balance experiences with employees.

- Support employees to achieve a good work-life balance by creating inclusive environments and a space to discuss issues and concerns.

- Make sure your working practices match the firm’s wellbeing goals or it can undermine trust in their authenticity.

- Lead by example by promoting initiatives that supports wellbeing as well as client needs and high standards.

What firms said

‘We are responsible for making this an environmentally sustainable culture and we need to have an authentic voice. This means telling partners that some things they were used to must change. We need to set the tone from the top as firms need to practise what they preach to attract talent.’

Many firms we met measured and rewarded individual employee performance with metrics related to the number of hours clients are charged annually. Chargeable or billable hours are widely used across the legal sector and most survey respondents, 66%, had billable hour targets.

Rewarding and recognising individual contributions was ranked as the second most highly valued feature of a positive culture in our survey. However, only a minority of firms had a specific reward and recognition scheme, or formal policies about recognising achievements.

Chargeable/billable hours targets

Financial performance is just one way of measuring success but is often the most common way firms show they value their employees’ contributions. However, targets that prioritise the financial value of employees has been under increasing scrutiny recently. For example, LawCare suggests that this model can have a detrimental effect on the mental health of some employees and fails to recognise and reward other valuable contributions.

Without adequate support and supervision, these pressures may mean some employees risk burnout, make mistakes or are susceptible to making poor ethical decisions on behalf of clients or acting without integrity.

When we asked respondents what one aspect of their work culture they would most like to improve; billable hours were, by far the most frequent answer. For example, a solicitor, less than five years’ PQE said: ‘Change chargeable/non-chargeable billing targets. It is not conducive in this century to be monitoring an employee’s work every six minutes. It is counterintuitive to the 'trust' and 'transparency' firms hype in an era of flexible/remote working.’

Most commonly, respondents highlighted difficulties balancing support for colleagues, with non-chargeable hours and meeting billing targets as their primary concern. For example:

- Solicitor, less than five years’ PQE: ‘Targets are so tight to meet when all non-chargeable expectations have been dealt with meaning communication with colleagues is minimal.’

- Associate solicitor: ‘If I must complete 7 or 7.5 chargeable hours per day, I don't have time for a positive workplace culture, a chat at the water cooler, to support and supervise more junior colleagues or to be involved in diversity networks or social activities. All these things are being demanded on top of chargeable hours/fee targets.’

Emphasis on financial performance

There were also concerns that focusing on financial performance meant that other work activities were undervalued, and client interests were not being put first. For example, a solicitor, less than five years’ PQE said they would like ‘less of an overarching emphasis on financial performance and more value on other aspects of work and relationships within the business.’

There was also recognition from some firms that financial measures can have a negative effect on culture and undermines good behaviours. This included concerns that it distracted from the quality of other work or could lead to unethical behaviour, such as overcharging. Crucially, this may be because they listened to feedback from employees.

For example, one firm told us they have a ‘People Board’ that reflects on survey results. They acknowledged that this revealed that their employees were not happy with being evaluated just on chargeable hours. As a result, they were looking at how they could best reward and recognise non chargeable work.

Good practice

Some firms we met measured performance with traditional hourly charging target structures. Targets or key performance indicators were also used to measure non chargeable, as well as chargeable activities but others were adapting them, or had removed them entirely.

Firms who were adapting targets introduced team targets to encourage a fairer allocation of work and better supervision from line managers or had reduced annual individual targets.

Others did not have any targets and had changed the way they manage and measure performance. They explained some of the advantages and disadvantages this provided for their businesses and their employees.

Good practice example from firms: Measuring achievements differently

Large international firm

‘There are no targets but there is personal responsibility. We record client time but do not have billing targets or targets for non-chargeable activities. This encourages employees to collaborate and share their time more generously with others who may need support. For us it’s a collective enterprise. Our competition is with other firms – not with each other.’

Large national firm

‘We asked our employees about what they thought about hourly billing targets and the feedback resulted in its removal. We reflected on the purpose of targets and our own strategy and decided that it stifles passion and creativity and sends an unhealthy message about what is important. We measure performance using a success criteria based on four metrics: trust among colleagues, trust among clients, impact on the environment and its community, and conduct as a purpose-led organisation.’

Small firm specialising in public law and human rights

‘When starting our firm, we considered how our policies could drive good practice. We decided that hourly billing targets encourages negative behaviours and doesn’t reflect the quality of work people carry out or how hard they work. Instead, their value is distilled down to six-minute units. However, because chargeable hours are so ingrained in our culture, it can be unsettling for new staff to think about how to prove their worth. Although it takes a while to get used to being valued in other ways, feedback from clients suggest that they see a better quality of work as a result.’

Small firm specialising in employment

‘We do not have chargeable targets because we want people to do their best work and financial targets hinder some people, especially trainees who can become too anxious. However, as a small firm we are also concerned that work in progress can turn into a ‘vanity project’ until it is charged. We have now proposed that department heads will have targets in future to manage our overheads as a growing business.’

Checklist

Does your firm apply any of the following strategies?

- Ask employees what matters to them when it comes to measuring success.

- Identify individual needs when rewarding performance.

- Assess whether billable hours targets pose any risk to your culture and values.

- Reward and recognise client satisfaction and other non-financial achievements.

- Supervision and appraisals discuss performance and achievements in a timely way.

- Ensure teams have the physical and psychological capacity to support peers.

Action: Focus on recognition and reward

- Celebrate teamwork, effort, and shared accomplishments as well as outcomes.

- Consider whether your performance management system motivates ethical behaviours and people to do their best.

- Ask for feedback and identify the business case for improvements.

- Include customer satisfaction, leadership qualities, teamwork, personal development, or contributions to allies and networks in appraisals.

- Demonstrate you value qualities that benefit your firm culture and wider community.

What firms said

‘Move away from emulating where you came from - targets, supervision, values and how you deal with clients, needs to be different. Think about your identity and be confident about what you're doing. If solicitors are happy, then you will get happy clients.’

Heavy workloads can also have an impact on working hours and mental health. Having manageable workloads was ranked as mattering the most in terms of a positive culture by our survey respondents, it was also acknowledged as being an area that presented a challenge to get right by individuals and firms.

Monitoring and discussing workloads

Supervision should include regularly monitoring and discussing workloads as this could impact on wellbeing as well as competence. Both small and large firms had regular file capacity meetings at least on a weekly basis and most used capacity management systems such as usually 'traffic light' tools to grade caseload volume as green, amber or red. Firms said this helped with metrics to provide oversight of the number and complexity of caseloads. Smaller firms said it helped to identify what new work they could take on.

However, fee earners and firms pointed out that while this can be a practical approach it may not be sufficiently nuanced to consider individual perceptions of what is manageable and may even create anxiety about performance levels.

For example, an associate solicitor indicated that although capacity assessments were self-reported, the perception was that there was little benefit in reporting a reduced workload. 'The goal is to be red rather than green in the traffic light system. If you are green, you might think there's a problem - why haven't I got anything to do? It also misses the point that you had a heavy workload the week before and were really stressed and need break or you need to be ready for court next week and will be busy.'

Good practice

Unreasonable workloads could affect competence and performance and ultimately, client service. Regularly discuss caseloads to identify challenges and be proactive about support if needed. For example, a firm highlighted that regular reviews of workloads enabled them to move resources to help busy fee earners or cover absences so that work is progressed.

A non-fee earner respondent told us: 'We have a live capacity table which shows all fee earners and indicates whether they are available for more work via a traffic light system. The rules themselves require tweaking but the idea is foundationally strong.'

Good practice example from a firm: Supporting emotional capacity

One small firm wanted to address issues that can affect wellbeing:

'We initially had a traffic light system based on volumes and complexity but realised that this did not take feelings about what complexity looked like to different people into account.

Managing stress is about our individual feelings, and so assessing workload capacity should not just be about finding a physical space for work but also the psychological space. We thought about what we wanted our capacity indicators to look like so that it is driven more by wellbeing rather than volume.

'We discuss individual needs so that work is now allocated in a way that supports strengths and manages weaknesses. It helps us to have a good grip on caseloads and make sure people are emotionally and psychologically supported as well as managing files - and this benefits clients. Taking on more work as a firm is also now a collective decision after people raised concerns about workloads. It was good to be challenged because it impacts them and their emotional wellbeing, which ultimately impacts on clients and the business.'

Checklist

Does your firm apply any of the following strategies?

- Capacity systems consider individual circumstances and wellbeing.

- Provide regular support and supervision to check capacity and workloads.

- Leaders provide assurances about work allocation, productivity, and achievements.

- Employees always have the resources to carry out their work well.

- Regularly obtain feedback about whether work is allocated reasonably or fairly.

- Oversight of workloads so that people do not feel overwhelmed.

Action: Define your culture

- What does your culture really look like and how could it be improved? Ask employees what they value and what doesn't work for them.

- Use this to create a short code or values statement that sends a message about your goals and culture which can easily be shared and recognised.

- Highlight ethical behaviours and explain why this is important so that everyone understands they are responsible for doing the right thing.

- Embed this in your policies, procedures, recruitment and induction materials, supervision meetings and appraisals.

What firms said

'Don't just publish a policy or statement - go through the process of explaining and taking people on the journey with you. It's a two or three stage programme and it takes time to embed values with your people.'

Some mistakes can arise from, or be aggravated, if concerns are not shared so that support can be offered, or environmental pressures such as heavy workloads. This is a concern because when people feel tired, stressed, or overwhelmed they are more likely to make poor ethical decisions.

Junior lawyers

A competitive environment can further increase feelings of anxiety around mistakes for junior lawyers. Survey respondents raised concerns about not feeling comfortable about admitting mistakes, mainly centred around the potential negative consequences of doing so. This included being unfairly blamed for issues that stemmed from a lack of supervision, being made an example of, or that small mistakes would be used against them in appraisals

For example, a trainee solicitor said they would not feel at all comfortable about admitting a mistake because ‘when I did, I got shouted at in front of a hundred staff …and you also get named and shamed.’

Another junior solicitor commented that ‘certain partners generally are quick to point the finger at juniors - and are notorious for under supervising and ignoring staff.’ However, notably the same junior solicitor also highlighted that they felt positively supported in their team saying: ‘My immediate manager is very good - I speak to him every day and he is very generous with his time and knowledge.’

Blame culture

Feedback from junior solicitors in our survey demonstrates how crucial it is for senior leaders to set the tone or risk creating a culture that focuses on blame and limits open dialogue. Remote working could also potentially lead to less confidence to report concerns if regular informal contact is not maintained between managers and employees.

For example, a respondent explained that a benefit of working closely with other people was that small issues or concerns could be dealt with informally. This was in comparison to ‘building up’ tension to create a space to speak about issues formally. Other concerns included:

- hearing negative comments from partners about colleagues who had previously made mistakes

- colleagues blaming others and distancing themselves from any blame

- firms having an overly competitive culture.

These comments highlight concerns that the culture in some firms could create a barrier to behaving honestly and openly when things go wrong, potentially leading to poor outcomes for clients and regulatory consequences.

Good practice

However, most survey respondents (76%) responded positively that they were very, or at least somewhat comfortable about admitting mistakes. This was also an area where we identified several examples of good constructive practice in firms. This suggests that firms are becoming more aware of the importance of encouraging the early disclosure of mistakes to manage risks.

Reducing feelings of guilt and anxiety

Working together with employees to resolve issues and using objective methods to find solutions to problems could help to reduce feelings of guilt and anxiety around mistakes. A firm said that ‘If there are any difficult cases, we usually suggest we pick it up with everyone not just one to one, so that it can be used a learning point for everyone.’

Many firms highlighted examples of senior leaders sharing stories of mistakes and personal challenges to reassure colleagues. For example, during a wellbeing event, a partner admitted being sleepless with worry after inadvertently responding to a phishing email, which resulted in a financial loss for the firm. They pointed out that the money was replaced, and they were promoted a few years later.

The value these messages hold for employees was acknowledged by many of our survey respondents, including three junior solicitors who said:

- Solicitor, less than five years’ PQE: ‘In a training session, someone from the senior management team told a story about a mistake ...and how his line manager supported him to fix it. He reassured us that this is the culture of our firm.’

- Solicitor, less than five years’ PQE: ‘A senior colleague shares any learning she has experienced from her own mistakes which reassures me that mistakes are normal, happen to everyone and can nearly always be remedied somehow.’

- Trainee solicitor: ‘Mistakes are acknowledged, advice is given on how to resolve the issue, not make the same mistake again... (and) how it could have been avoided. I like that I am encouraged to put it right myself and feel empowered.’

Mistakes can be viewed positively when they are managed constructively. Focusing on reaching solutions collectively and learning from mistakes or near misses empowers people to be open about concerns. One firm said: ‘It’s about having a dialogue and listening rather than telling. It should come from a place of wanting to help people reach the right outcome rather than punishing people for mistakes.’

A partner at a large firm told us that they use problem solving techniques to help people work through difficult issues constructively and identify learning points as well as next steps: ‘We talk about mistakes in a constructive way. We reassure and address proactively the issue and then once that is in hand, look at root cause on the ‘5 Whys’ to identify what went wrong and if we can learn from it.’

Create a no blame culture

Having supportive and compassionate leaders who respond to challenges positively and lead by example helps people to feel trusted and valued. Some firms discussed having values embedded into performance reviews and a recognition scheme to reward and acknowledge positive behaviours. Another firm told us: ‘we try to treat mistakes with humanity and have a code of conduct that governs behaviour.’

Examples of strategies firms used to support employees and create a no blame culture include:

- discussing how they deal with potential claims and insurance notifications

- one to one meetings so that concerns can be discussed informally at an early stage

- providing a form for recording breaches on every matter

- working together to resolve issues or dealing with the issue on their behalf

- discussing ethical decision making in team meetings and sharing decisions from the Solicitors Disciplinary Tribunal (SDT) during inductions

- making sure employees know who to approach when they identify a mistake

- creating a safe environment to raise concerns by openly discussing mistakes in team meetings or having a reporting system, such as a confidential mailbox.

Good practice example from a firm: Supporting junior lawyers

A solicitor, less than five years’ PQE, at a mid-sized firm said:

‘After a challenging time at a previous firm, I joined a new firm as a newly qualified solicitor. I hadn’t been there very long when I was tasked with dealing with a settlement agreement. There had been a verbal agreement that it should be costed a higher rate but in error I recorded the bill at a lower rate. I was in a new job and really concerned when I approached my line manager.’

‘My manager was very reassuring, I didn’t feel criticised, but my concerns were not dismissed, and they helped me to find a straightforward solution. This approach at such a critical starting point in my career has always encouraged me to be comfortable about being open and honest when making mistakes.’

Checklist

Does your firm apply any of the following strategies?

- Create a no blame culture by focusing on learning from mistakes.

- Analysis tools are used to work through problems and find constructive solutions.

- Use any near misses (anonymously) as learning points in training

- Share personal stories and experiences to encourage others to be open in return.

- You tell employees what to do and who to speak to if mistakes are made.

- You discuss relevant real-life examples of ethical issues in training or team meetings.

- You explain how claims are managed or resolved by insurance.

Action: Establish wellbeing systems and controls

- Create wellbeing policies that highlight no blame cultures, work allocation procedures, available support and how to raise concerns.

- Use risk assessments for different work areas and clients to monitor and identify wellbeing risks and keep records of they are being addressed.

- Good oversight of systems and controls with senior boards or steering committees, underpins an effective wellbeing strategy or values statement.

- One to ones, training, and supervision help to manage ethical and mental health risks.

What firms said

‘Our expectations are set from the start. We have a training programme on compliance with check in points for all to reinforce learning. We also keep records to spot patterns and trends and if we keep getting the same question, we will identify a learning gap.’

Further help

- Read our enforcement strategy for more on when you should report issues.

- Read our guidance about putting matters right when things go wrong and own interest conflicts.

- Call or web chat our professional ethics helpline for confidential advice.

- Visit your health, your career.

Another common theme from our survey was experiencing unacceptable, inappropriate and/or uncivil behaviour at work. This can include a multitude of harmful behaviours such as, microaggressions, bullying, discrimination, harassment, or inappropriate sexual conduct.

Speaking out about poor behaviour

Prioritising wellbeing and re-examining working practices can build a more resilient and positive culture, however, if concerns do arise firms need to address them promptly. Being able to speak out about poor behaviour and unfair treatment at work without fear of stigma or reprisal, is crucial for any firm that wants to manage risks and maintain the trust of its employees.

Seventy-eight per cent of respondents said they felt comfortable about raising a concern about unacceptable behaviour at work. This suggests that most people have confidence that any issues will be dealt with fairly and positively by managers.

Positive examples of good practice highlighted how managers had supported individuals without judgment. A solicitor, less than five years’ PQE, said: ‘A partner made me feel uncomfortable and targeted in their abrupt communications. I raised it with my manager who reassured me and spoke to the person directly. I felt supported as it would have been easy to dismiss my concerns, but my manager was prepared to stick his neck out.’

Barriers to raising concerns

However, our analysis of survey comments also shows that people who felt less confident about speaking up about concerns had experienced barriers including:

- not knowing how to report incidents

- having concerns handled badly; including complaints being disclosed to other colleagues or forwarded directly to the subject of the complaint

- complaints being dismissed, or minimised by managers

- being blamed, or there being no consequences for the culprit.

A solicitor, six-plus years’ PQE, commented: ‘It is not an environment where I feel I will be treated fairly following such a conversation. I raised the issue of bullying when I was a junior lawyer, and nothing was done about it.’

Firms also told us of the following potential risks if employees didn’t speak up:

- Individuals avoiding work which may lead to delays in responding to clients.

- Issues not being dealt with early on, leading to an increase in formal complaints.

- If people are stressed, they are more likely to make mistakes.

Clear values and policies

Clear messaging about values, or training about ethical behaviours helps create a culture of integrity and psychological safety which can empower people to come forward and raise concerns. However, only 48% of respondents to our survey agreed that their firm’s values and visions were widely understood and lived by all working there.

Just half of the firms we spoke to provided training on acceptable behaviour and most provided it only during inductions or just to partners. This could affect how positively concerns are responded to by managers and may diminish employees’ trust and confidence in procedures.

Senior leaders play a critical part in managing workplace risks by supporting people to feel safe about speaking out about behaviour such as bullying. Having policies and procedures is just one aspect of dealing with negative behaviours. To maintain trust and confidence firms need to show that complaints will be treated seriously.

Non-fee earners and junior lawyers’ experiences

Junior lawyers and non-fee earners may be more vulnerable to being targeted by bullying or other forms of uncivil or unacceptable behaviour because of the hierarchical nature of work cultures in some firms.

Some non-fee earners reported that they felt’ ignored’ or were ‘treated as unimportant’ and this affected how confident they felt about having their concerns listened to by managers. One non-fee earner said that a better flow of communication between employees and managers would enable them to voice their concerns.

The JLD told us that junior lawyers often feel less confident about speaking up and challenging managers because they have a more precarious position in the workplace. They may worry about jeopardising their careers, particularly if they are in a training contract and risk being seen as troublemakers.

Some respondents also highlighted that inappropriate behaviours were accepted because of the fees individuals were bringing to the firm. For example, a non-fee earner said: ‘A lot of the time it doesn't feel worth reporting issues because firms may choose the fact somebody is a valuable fee earner over their culture...you feel like you shouldn't raise issues so as not to cause friction or face potential mistreatment further down the line.’

A junior lawyer similarly told us that their culture would be improved if there was more ‘respect (for) trainee solicitors and paralegals and (they) avoided using bullying or intimidating tactics to put them down.’

Good practice

Promoting autonomy can help flatten hierarchical cultures and support greater trust and respect. As one solicitor, less than five years’ PQE, responded: ‘I’m a junior lawyer and there is a hierarchy but there is an equality of working arrangements that is different to other firms. We respect everyone and treat everyone the same. Working in a mature environment where there is a great deal of trust and being treated as an adult makes me feel valued and happier - and as result I feel motivated to give more to my work.’

Values must be aligned with the behaviours of leaders if they are to be perceived as trustworthy. One firm said that they made sure their values were embedded by having a ‘transparent, flat structure’. They described this as ‘a practical manifestation of their respect for others and cultural goals.’

Support a culture of integrity by addressing and calling out poor behaviour when it is brought to your attention. As one solicitor put it, ‘If people turn a blind eye, then things don’t change.’ It’s important to be seen to be doing the right thing and this ensures policies appear credible and decisions are consistent.

Having transparent processes and multiple informal and formal options for reporting can also help to encourage people to speak up. Approaches used by firms to make sure formal policies and controls were effective included an anonymous confidential mailbox and a ‘Listener’ programme to provide an informal contact to raise concerns with.

Good practice example from a firm

A mid-sized firm said:

‘We think that the formalised nature of the grievance process can sometimes be a disincentive for people to raise complaints. We created the ‘Guardians Network’ in conjunction with the Old Vic Theatre to provide more informal opportunities to speak out.

‘The programme offers training to organisations to help people provide confidential advice to any employee who might be considering raising a complaint about behaviour or cultural issues at work. They help them to escalate concerns appropriately.’

Checklist

Does your firm apply any of the following strategies?

- Publicise several formal and informal options to report concerns safely for example via a confidential mailbox, hotline, or a trusted individual.

- Reward positive behaviours that demonstrate treating others with respect and dignity.

- Train managers how to support colleagues making complaints and to address concerns positively.

- Send clear and unequivocal messages that unfair treatment, bullying, harassment, discrimination, or victimisation will not be tolerated.

- Use role plays and training to highlight what ethical behaviour looks like.

- Keep records of reports and how they were addressed.

Action: Safe environment to raise issues and concerns

Create an environment where people feel safe to raise issues and concerns without fear of any penalty with clear channels of communication.

- Empower people to speak up by producing guidelines that explains that people should raise concerns and how to do it.

- Provide peer support or a buddy system so that colleagues also have an informal route to discuss issues when things go wrong.

- Show you value feedback by receiving and addressing concerns positively.

What firms said

‘Be sympathetic to both parties, try and take the worry and emotion out of situation as much as possible. Keep matters confidential, follow firm procedures, and make sure you are ACAS compliant. It only takes one bad egg in an organisation to impact morale if others see that concerns are not being addressed and properly dealt with.’

Further help

- Bullying in the Workplace

- Workplace bullying and harassment

- LawCare - Bullying in the workplace

- Mind - Difficult work relations

- Read our guidance on your reporting obligations

- Read our guidance about reporting serious misconduct, sensitive information, or risk to the public

- Read our guidance about what to expect when we investigate reports.

- Make a report to us.

One to ones and supervision meetings can manage risks by creating a space for dialogue with employees about their workloads, capacity, and competency. Fee earners also told us that regular supervision helped them to feel psychologically and emotionally supported at work. Therefore, it can also be a valuable source of support and contributes to personal wellbeing.

In addition to supervising the quality of work, supervision should include discussions about any worries, concerns, near misses, or development needs, as this could impact on wellbeing as well as competence. Setting aside time to discuss pressures could also help to identify ethical concerns and prevent mistakes happening.

However, not all staff have access to regular support. A junior solicitor commented that their culture would be improved with ‘more structured supervision and a designated mentor for junior staff. It would provide regular feedback to reassure me I am doing my job correctly or help me learn how to do it better next time.’

Supporting lawyers at all levels

Maintaining informal, safe opportunities for guidance and support is critical. Some respondents noted that remote working made support more ‘formalised’, and they had to be more proactive about scheduling meetings, rather than having a quick ten minute catch up.

This was particularly an issue for junior lawyers because their visibility had been reduced, leading to less informal opportunities for training and networking. One firm resolved this by sharing regular welfare surveys for junior employees and encouraging more online shadowing in calls to clients.

Junior lawyers also mentioned the negative impact of remote working on networking and the social aspect of working lives. Social occasions can be particularly important for them because they help people to bond as a team and find supportive peers and mentors.

Even experienced solicitors must undergo learning and development, both for their own progression and as part of their continuing competence requirements. Therefore, they also still need regular support, feedback, and guidance to help plan upcoming work. A senior solicitor discussed the huge learning curve they experienced managing client demands at the same time as their own caseload.

Another solicitor said ‘a big part of my day is supervision and feedback. I'm 7 years qualified but still need to ask questions and will speak to the partners about anything complex like pleadings.’

However, some senior fee earners reported that there was often a culture of people being ‘too busy’ which meant it was difficult getting timely supervision. They commented that they had to be proactive about seeking support from partners and had day to day support from peers.

Training and development

Almost half of our survey respondents (48%) said that having regular training and development opportunities helped create a positive workplace culture. A significant number also said that time off for study and professional development helped create a healthy and balanced working pattern. Most firms had a development programme in place, but some fee earners indicated that career paths were not always transparent.

Training supports employees to make ethical decisions and understand their regulatory obligations. Seventy-five per cent of firms provided training on ethics and integrity to employees to manage compliance risks. Respondents told us that ethical training should be realistic and draw on real life examples from their working environments not just SDT cases.

Lawyers of all levels mentioned that their teams were a vital source of day-to-day support. Working together helps learning and social cohesion. A solicitor, less than five years’ PQE, said: ‘Communication and catch ups are key and it feels a very collaborative environment to be in. I feel very supported by my team and feel able to communicate with them. There is also wider firm support and we had partners mentoring us when we qualified.’

A smaller number of firms provided mentoring, coaching or peer support and buddy schemes for trainees and partners. Peer support can help people to engage with others outside their immediate team and brings authenticity to conversations. One respondent, solicitor with less than five years’ PQE, highlighted that their working environment had been improved by in house coaching and mentoring and that ‘moving to a firm with a positive workplace culture and great leadership has been astounding.’

Approachable well-trained managers

Many respondents highlighted the importance of approachable managers who have time to provide effective emotional support for colleagues. However only a small number of firms offered dedicated training for managers about how to deal with inappropriate behaviour or to create a no blame culture. This could mean that early opportunities to identify and address risks or provide support could be missed.

Good practice

Some firms spoke about how they supported senior leaders by building a learning culture with training and initiatives such as reverse mentoring and 360 feedback. Partner reviews were used to make sure fee earners were supported to develop their careers.

Mentoring and coaching schemes can provide more informal opportunities to speak to senior colleagues about their work and personal development. Buddy systems with peers helps to encourage collaboration. As one firm put it, this means: ‘There are lots of people to turn to and learn from.’

A respondent said that her firm encourages people to work in teams which allowed people to step into team leader positions and develop their leadership and management skills. One firm said: ‘We do not have targets - we recognise skill sets. We put people in line management roles who can be good managers and we understand they may not be able to manage a caseholding at the same time.’

A small firm were conscious that face-to-face supervision is difficult to replicate when working remotely. They introduced a regular virtual caseworking meeting so that senior and junior lawyers could meet and discuss file reviews and any problem cases.

Other examples of good practice to manage this risk included:

- focusing on psychological safety in supervision to enable people to speak up when they are not sure about something or need help

- developing a new supervision policy to focus on coaching to encourage dialogue

- increasing supervision and catch-ups for junior lawyers working remotely

- an on-going training programme to support junior lawyers

- a buddy programme for partners during lockdown to provide support and help anxiety

- leadership training with a focus on values and soft skills to help leaders engage and support their team.

Support for an associate solicitor

A fee earner at a mid-sized firm said:

‘When you are a trainee, you have a buddy and then you become a buddy to the next cohort of trainees. There are also volunteer mentors, but it comes down to personalities though as to whether it works or not. Everyone below five years’ PQE was partnered up with a senior associate in a different team as a source of support. This worked well because it removed some of the immediate politics of support. However, this support fizzled out when I became more senior and because they were removed from the work in my team there is a limit to the insight they can offer.

I still feel I need support but as the source gets more senior too, that can pose challenges in terms of availability and time. But if I do need to speak to a partner, they are approachable and can be accessed. There’s a phone call to touch base and I have weekly meetings with my line managers. We email information every Monday morning about our case holding and then we have a follow up team meeting to check capacity.

‘They trust me to check in with them and I have autonomy to manage my own work. I tend to discuss cases with my team informally but as an associate a large part of my work is unsupervised. But that’s because only I know about some areas of my work and so it’s difficult to get the supervision.’

Checklist

Does your firm apply any of the following strategies?

- Regular one to one meetings are scheduled to discuss training needs and wellbeing.

- Training on ethical, compliance or regulatory concerns and any near misses.

- Embed a learning culture and offer supervision and mentoring throughout careers.

- Transparent career pathways and development plans for lawyers at all levels.

- Remote workers have regular opportunities for informal peer support and learning.

- Managers are trained and have the time and resources to support employees.

- Psychological support for employees working in emotionally demanding work areas.

Action: Embed values and ethics

- Senior leaders consistently model behaviours that promote respect and integrity.

- Engage with employees to identify shared values and incorporate them into all policies.

- Create a behaviour or ethics code that tells people the right thing to do.

- Monitor and record ethical risks with risk assessments and record any actions taken.

- Recognise and reward positive behaviours that demonstrate your values.

- Include values in appraisals and ethics in learning and development programmes.

- Empower employees to challenge leaders and clients to manage ethical dilemmas.

What firms said

‘Our values were set by thinking about what they meant to everyone in the firm. We consulted with everyone in focus groups. The core of our performance reviews is based on our values. Look at what your current culture is and its unwritten rules.’

Further help

- Read our guidance on Continuing competence and accreditation

- Mind - Wellness Action Plan for Managers

Firms should act in a way that encourages equality, diversity, and inclusion. Creating an inclusive environment helps people feel that they can be authentically themselves at work and belong to a community. This in turn, means that they are likely to be more engaged and motivated, leading to better outcomes for clients and therefore businesses.

Benefits of an inclusive working environment

Most respondents felt that their firm created a positive work environment by being inclusive and valuing the diversity of employees. Culture is a collective experience, and everyone has a part to play in creating it. Fee earners highlighted that networks supported inclusive work environments and helped individuals to be themselves.

Employee networks

Some firms indicated that they still needed to make progress in some areas such as introducing network allies but most medium to large firms had employee networks.

A solicitor, less than five years' PQE, commented: 'We are improving all the time in terms of having more networks for different groups. People in the industry now expect more and my firm has recognised the gaps in networks and support. They bring people together and means as a gay person, I can talk openly about my life and my views on our recruitment. It gives people a sense of belonging.'

Networks help people to connect with each other to discuss shared experiences. A junior solicitor remarked that the pandemic has changed cultural expectations and the divide between personal and professional life: 'Gone are the days when you didn't talk about your personal life, especially since Covid-19. It's important for people to bring their real selves to work. I had concerns about joining a large firm. Would it be too posh, alien, and corporate? But networks helped to bring us together and form bonds.'

Greater diversity and social mobility needed

Other fee earners also noted that firms had implemented more inclusion activities since the pandemic. But still felt that there was room for greater diversity and social mobility in firms, particularly among senior leaders:

- Associate solicitor: 'There is still an under representation of Black and minority ethnic people in higher positions. The gender imbalance is getting better, but I still feel conscious about it, and it really sticks out to me and to others.'

- Associate solicitor: 'Employees aren't very diverse in terms of trainees' backgrounds, particularly in terms of race and social mobility - they are missing out. Everyone is the same with the same opinions and they all think from the same perspective and by doing so they are missing out on good people.'

Creating a work culture that supports acceptance and inclusion is particularly important when people are working away from offices. Two firms acknowledged that while they had made good strides to improve communications since the lockdown, they still needed to improve the mechanisms that helped employees to feel a sense of belonging.

Good practice

We saw high levels of engagement and collaboration at firms and the evidence suggests that this led to positive and meaningful change. Many firms focused on improving inclusion by bridging the communication divide between senior leaders and employees. For example, a firm introduced a gender balance programme where male partners are mentored by a female colleague to make sure they are aware of different perspectives.

Firms told us about employee network representatives regularly attending a partner's meeting for feedback and at another firm, partners participating directly in employee networks. Firms said that these discussions were very open, and people were prepared to challenge partners and informed them about other issues. This helped to improve their approach and fed into their recruitment strategies.

One partner at a large firm commented: 'I was blind to the issues around 'Black Lives Matter'. A member of staff in one of our networks said that I need to say something about it and action it too. I felt that it was helpful to have that engagement because having a partner speak out on issues is a powerful way of making a noticeable change. It's also a really good way of modernising our ideas and approach.'

Showing you value and accept other views and experiences helps to foster a supportive and inclusive working environment. One large firm said: 'People find it refreshing when the leadership team are open to learn and open about their vulnerability. Attend support groups but don't lead them, learn from them. Ask questions and incorporate new ideas that people think are important.'

Good practice example from a firm and fee earner: Inclusive language

A partner at a mid-sized firm and a fee earner from a small firm talked about their experiences of listening to employees and being listened to by managers when they highlighted issues around inclusive language at work.

Mid-sized commercial firm

'We listened to our staff and removed gender specific pronouns in salutations in letters. It's important that business leaders understand that culture is a business priority because what we sell is people - it's a talent-based sector. Certain partners initially pushed back and dismissed it as 'woke'. But we had to address and cut through personal bias and be more forward thinking and progressive. Some people may not see why this is important because it doesn't affect them, but we started to notice a gradual progression to an acknowledgment that less gender specific language is expected.

'Small changes that acknowledge individual experiences can make a big cohort of your population happy, and costs nothing. We need to listen to our people and the fact is - attitudes are changing. Culture is not static it evolves and means different things to different people. As a firm you need to roll with that and be progressive if you want to be a firm of today and not stuck in the past.'

Fee earner at a small firm

'I changed my pronouns, and everyone was supportive when I told the firm. The partner's first response was to check how their policies used pronouns and suggested training for everyone and so I shared some information with them. Some people are never 'out' at work in case they are not respected - but here, I felt there was a willingness to learn, listen and teach each other with kindness and support.'

Checklist

Does your firm apply any of the following strategies?

- Promote equality and equal treatment with values statements, wellbeing strategies and inclusive recruitment policies.

- Invite your colleagues to become inclusion allies and mentors.

- Focus on a healthy, supportive working environment that promotes wellbeing.

- Demonstrate your commitment by signing the Diversity and Inclusion Charter.

- Create a sense of community with employee networks and peer support groups.

- Senior leaders are proactively involved in diversity and inclusion initiatives.

Action: Engage with colleagues

- Show you value employees' experiences by asking how you can support them.

- Attend networks to learn from colleagues and share personal stories.

- Be transparent and communicate about culture regularly in newsletters.

- Develop culture initiatives 'bottom up' with employees and test them in focus groups.

What firms said