The factors influencing differences in outcomes by ethnicity in legal professional assessments: A systematic literature review

Published 2 June 2023

This report is a summary of the first phase of our research to better understand the reasons differences in professional assessment outcomes by ethnicity. It also sets out the next steps for the second phase.

In this first phase of this important work, the University of Exeter reviewed in detail over 250 UK and international academic, government and professional reports and articles. They also consulted with 25 experts, including other academics, regulators and members of the profession.

Open allOur annual education and training monitoring reports show long standing and widely-acknowledged differential outcomes for candidates from different ethnicities in legal qualifications. This troubling pattern is also the case in other countries and in professional assessments in many other sectors, as well as in school, further and higher education. It is often known as an 'attainment gap' or an 'awarding gap'.

We know this has a real impact on individuals and on the wider profession, so we want to understand better what is happening. We commissioned the University of Exeter to conduct independent research to better understand the factors driving differences in outcomes in legal professional assessments. We can then share this evidence, so that we and others can consider how best to address the issues.

The legal assessments that are in scope of this research are those that pre-date the Solicitors Qualifying Examination (SQE), such as the Legal Practice Course (LPC) and the Graduate Diploma in Law (GDL).

We anticipated seeing a difference in outcomes in the SQE and we are monitoring this by diversity characteristics. Our quality assurance processes include reviewing how we make sure that the examination itself is fair and free from bias, and we have a detailed evaluation programme for the SQE. We will take on board the findings from this research as we continue with our evaluation programme.

The University of Exeter's review has confirmed the complexity of the factors that might explain the differing outcomes in professional assessments. The review also confirmed that a variety of possible solutions have been identified by others, although not all of these have been tested.

They found strong evidence that the following influences exam outcomes positively and/or negatively to varying degrees:

- education journeys, including:

- any positive or negative experiences at school, college or university

- how well students feel that they fit in at their place of education

- the availability of support in education and work for minority groups.

- students' beliefs in how they might succeed in a profession, which includes whether they think that:

- a profession is elitist and affected by the privileges that some characteristics are more likely to offer some people (such as being White and/or male)

- there are barriers and/or opportunities to entry and progression based on characteristics with which they identify, such as social class and ethnicity

- the experience of being part of one or more minority groups, which can include being rejected or discriminated against because of those characteristics

- negative experiences can lead to the need to make extra effort on ‘coping strategies' to achieve positive outcomes in academic and professional settings

- life circumstances, such as families' socioeconomic status and neighbourhood.

They also found that there:

- were varying definitions of the attainment gap, ethnicity and other characteristics, which makes it difficult to compare findings and draw conclusions from different studies

- • have been several interventions in academia, and across different sectors, to address the differing outcomes, from which others might learn, although not all were evaluated to find out whether they were effective

- was limited literature on:

- the lived experiences of Black, Asian and minority ethnic candidates of legal professional assessments in England and Wales

- how the different factors that might explain the differing outcomes interact with each other

- the causes of the differing outcomes in legal professional assessments.

This is the first piece of research that brings together the wide variety of potential factors relating to professional assessments, especially where these are relevant to legal assessments. Past research tends to focus on a limited number of factors.

This extensive review is an important stage in the research and has helped the University of Exeter to design a theoretical model of the reasons that could explain the differing outcomes. They will test this model, and address the limitations of the past literature, in phase two.

The researchers will use data analysis, interviews and surveys to test whether and how the various potential factors explain the issue and to understand people's lived experiences. The research is likely to produce insights that are useful in other sectors too, as it may unpack wider societal and structural issues.

Phase two will continue through 2023. We expect the research to be complete by the end of 2023 and for the final report to be published in spring 2024.

The final report will bring us closer to understanding what we and others can do to address the differing outcomes by ethnicity. Given the complexities set out by the researchers, it is likely to need several activities and changes, potentially from many different organisations. And any improvements will take time. In commissioning this research, we are committing to playing our part in bringing about lasting change.

If you are interested in contributing to the project or hearing more about it, you can provide your details using this short survey.

Report by the University of Exeter

Associate Professor Greta Bosch, Professor Ruth Sealy, Dr Konstantinos Alexandris-Polomarkakis, Dr Damilola Makanju, Associate Professor Rebecca Helm

Acknowledgements

The research team at the University of Exeter would like to thank everyone involved in this research project and the production of this report: the Solicitors Regulation Authority (SRA) for their funding, guidance and support, the project’s External Reference Group who offered us support and advice, as well as Dr Janice Hoang and Julia Fernando for their assistance with the research for this report.

Preliminary remarks

What we looked at

There is a long-standing pattern of attainment gaps for certain groups in legal professional assessments such as the Legal Practice Course (LPC). Such gaps particularly affect Black, Asian and minority ethnic candidates. Attainment gaps are also evident in other sectors with professional assessments, in education more broadly, and, as anticipated, in the first sittings of the newly introduced Solicitors Qualifying Examination (SQE).

The Solicitors Regulation Authority (SRA) commissioned this research to better understand the factors driving the attainment gap for these groups in legal professional assessments. It also wanted to consider whether there are steps that could be taken by the SRA and others to address the factors that underpin this widespread picture.

What we did

A detailed examination of specific professional assessments will not be conducted as part of this research, although these may be discussed to some extent where necessary. This research focuses on factors other than characteristics of assessments themselves that influence attainment gaps. Although we do give some consideration to how methods of assessment can contribute to the attainment gap, including among different ethnic groups.

We also discuss studies returned in the systematic literature review (SLR) that touch on methods of assessment, including their possible impact on attainment. More specifically, since a separate, independent and in-depth evaluation of the SQE will be commissioned by the SRA, this is outside the remit of this commissioned research.

Overall, this report of the SLR synthesises pre-existing studies that help us to better understand the potential reasons for the attainment gap and potential interventions to address it.

Categorisation and terminology within the review

We use the term ‘minority ethnic’ to refer to people from minority ethnic backgrounds. Although this term refers to all ethnic groups, most of the studies seen in the SLR did not discuss white minorities. We refer to specific groups where possible so that the reporting is as accurate as possible and does not hide differences within these broad categories.

For the research question of the SLR, we relied on the term Black, Asian and minority ethnic. This was done in order to capture as many results as possible due to the broad use of the aforementioned term in the literature. It is also a term used by the SRA in its publications and communications. The SRA also recognises the difficulties of appropriate terminology.

When describing the studies included in this review, we tend to use the terminology as referred to in the study cited. This report also uses terminology of the studies cited when referring to other protected characteristics, such as, for example, sexual orientation or gender.

We acknowledge that the terminology used for minority groups in this research (as would be with any other group defining term) was from the outset, and continues to be, problematic. This will be compounded by ongoing social change, organisational change, inter-group and identity change. Furthermore, there is a need to think about how we categorise and how we make that categorisation work for (ie conceptualising and operationalising) white ethnic (sub- ) groups.

We will use the categorisation we have been commissioned to research but acknowledge the problematic operationalisation of limiting terms such as this. We will continue to think about terminology throughout the duration of the project. We hope that our research findings will help us come up with conclusions/suggestions about the usefulness of various terms in research and other settings. In the meantime, to mitigate this immediate challenge, in our Workstream Two we will offer space for individuals to identify themselves. We will also continue our dialogue with stakeholders and to critically challenge the terminology of group categorisations.

Executive summary

This is the first report of a research project commissioned by the Solicitors Regulation Authority (SRA). The project aims to better understand the reasons for differential performance by candidates from Black, Asian and minority ethnic backgrounds in legal professional assessments in England and Wales. This is also known as the attainment gap.

This report details the findings from Workstream One of the project. The findings were drawn from an SLR that included 215 articles from academic literature and 43 practitioner-focused reports published since 2010.

The SLR showcases the existing knowledge on the ethnicity attainment gap, drawing on literature from across multiple disciplines and examining causes at the:

- individual or micro level (relating to candidates themselves);

- community or meso level (relating to the community and infrastructure surrounding candidates); and

- societal or macro level (relating to social structures and institutions). The research question underpinning the SLR was the following:

What does existing literature tell us about the attainment gap of Black, Asian and minority ethnic candidates in legal professional assessments?

Themes in the literature

Literature examined as part of the SLR revealed important insights relating to four main themes, which emerged from the review process.

The four themes are the following:

1. The challenges of terminology:

An important finding of the SLR relates to the different definitions and categorisations used to describe both the focal point of interest (the attainment gap) and the population of interest in this project. The definitions and categorisations varied mainly depending on the country of the study. Variations were also observed regarding the notions of socioeconomic status and class. Importantly, some research included all minority ethnic groups in one category, obscuring potentially important differences between different minority groups.

The lack of consistency in terminology and categorisation presents challenges for this project, as well as for any other future research on the topic.

2. Socioeconomic and educational background:

The SLR revealed substantial scholarship on how a candidate's background and education in the years preceding legal professional assessments can constitute important factors that may influence their assessment performance (and relatedly the attainment gap).

The surveyed literature detailed a series of mechanisms that may affect attainment, such as:

- institutional education systems;

- socioeconomic background;

- language competence; and

- neighbourhood and family.

Importantly, substantial attainment gaps persist at university level, which is likely to feed through into professional assessments. The literature also suggested that minority ethnic students may struggle to feel like they fit in well in some educational environments and that these issues of fit may influence attainment.

In the educational context, a range of factors (at the macro, meso, and micro levels) can have a clear impact on attainment. These include:

- inclusive curricula;

- relationships between staff and students;

- the notions of social, economic and cultural capital; and

- psychosocial and identity issues.

3. Professional and employment contexts:

The literature demonstrated that perceptions of a profession and individual ‘fit’ within it can influence performance on professional assessments. This could for example be through influencing self-efficacy (belief in one’s own capacity for success), motivation, aspirations, and related choices.

As a result, the literature suggested that the current characteristics of the profession are likely to have important implications for attainment in professional assessments too. This is even though the legal profession relates more directly to the post-qualification stage.

In the legal context, several factors may trigger these issues, such as:

- perceptions of the legal profession as elite and stratified;

- barriers to entry (such as the high costs associated with legal professional qualifications);

- a lack of acknowledgment that factors other than merit influence progression;

- the continuing influence of social class, privilege and whiteness in career success and progression; and

- negative lived experiences leading to particular coping strategies.

4. Interventions:

The SLR also yielded potential interventions to address the attainment gap.

These varied in terms of level, context and implementation.

Overarching themes

A number of overarching themes in the literature cut across several of the broad categories discussed above. These bring together factors that can explain the disadvantages that Black, Asian and minority ethnic individuals face in different contexts and contribute to the attainment gap.

The identified overarching themes are:

- Social and cognitive factors in education and career, including self-efficacy beliefs and outcome expectations;

- Implications of holding minority status, including experiences of rejection and discrimination;

- Implications of holding multiple marginalised identities (known as intersectionality);

- The normalisation and privilege of whiteness and maleness/masculinity in dominant culture, as well as practices that indicate low representation, low participation and disadvantage for individuals who do not have these characteristics;

- The need to employ coping strategies to manage marginalised identities, meaning using extra effort to achieve positive outcomes in academic and professional settings;

- Lack of integration and unsupportive climates for marginalised identities in academic and professional settings.

Omissions in the included literature

The SLR identified omissions and limitations in the current literature. The inconsistency in the terminology employed, as well as the categorisation are a challenge. More specifically, the choice of terms is not always justified and could lead to either oversimplification or complexity. Furthermore, these disaggregation challenges hamper like for like comparisons.

To better understand the attainment gap in the context of legal professional assessments, it is important to identify three key understudied aspects of the issue:

- The SLR revealed a lack of incorporation of the voices of Black, Asian and minority ethnic candidates in studies of legal professional assessments in England and Wales. This represents an important omission in fully understanding causes underlying the attainment gap in question.

- The wide range of potential attainment gap contributors are often examined separately, meaning knowledge on how they work together and interact with each other is limited. A multi-level approach, bringing together multiple potential causes of the gap, and their interaction with one another, is important in gaining a cohesive understanding.

- Research is needed to examine how the potential causes of the attainment gap work specifically in the context of legal professional assessments. The legal profession’s potential role in the attainment gap problem has for the most part been overlooked, something that this project intends to address. Detailed empirical studies in this area are vital to enhance understanding of how causes work together in the context of legal professional assessments specifically.

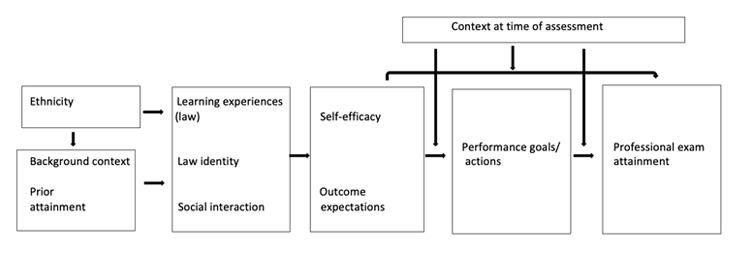

The importance of social and cognitive processes revealed by the literature review suggest that a framework informed by Social Cognitive Career Theory (SCCT) may be promising in structuring empirical work on this topic. At the same time, it will also be helpful to incorporate some additional constructs to this framework. Such constructs include, for example, how people identify with the legal profession, which we refer to as law identity.

SCCT is discussed in more detail in sub-sections 3.3 and 6.1 and relates to a theory that explains the development of academic/vocational interest, the pursuit of career choices and the persistence and performance in that academic/vocational field.

Workstream two plans

The analysis of the SLR undertaken in this report lays the foundations for the follow-up research of Workstream Two.

Taking into account the challenges and omissions identified when reflecting on the findings of the SLR, the follow-up research aims to:

- Adopt a nuanced approach to terminology and categorisation by disaggregating where we can and by taking into account intersectionality;

- Focus on highlighting the lived experiences of individuals themselves;

- Drawing on prior qualitative work, go beyond set categories of race through self- identification and identity. For example, this will be achieved by interviewing participants who will be asked to self-ascribe their ethnicity, without any pre-defined categories;

- Adopt a broad approach incorporating influences at multiple stages of an individual’s education and career development;

- Establish whether there are any links between the legal profession itself (and perceptions of it) and performance in legal professional assessments;

- Draw on SCCT to examine the multiple causes underlying the attainment gap and how these causes work together to influence attainment.

Introduction

Each year the SRA publish an education and training monitoring report relating to their transitional routes (LPC, Qualified Lawyers Transfer Scheme and Equivalent Means). The reports show a widely acknowledged and persistent difference in legal professional assessment outcomes by ethnicity, insofar as solicitors' qualifications are concerned. This is commonly known as the attainment gap and is not unique to legal professional assessments. It affects all levels of education and is a global phenomenon.

UK data on degree awards from the past decade show figures changing but with persistent gaps.

Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE) 2010 data (Higher Education Funding Council for England, 2010; Times Higher Education, 2010) shows that the proportions of students awarded Upper Second (2:1) or First (1st) class undergraduate degrees in the UK were different by ethnicity:

- 62% of white students were awarded a 2:1 or 1st class undergraduate degree;

- 37% of Black students were awarded a 2:1 or 1st class undergraduate degree; and

- 42% of Pakistani and Bangladeshi students were awarded a 2:1 or 1st class undergraduate degree.

Data from Advance HE (AdvanceHE, 2017) reveals that across the UK in 2015/16, the attainment gaps are largest in England. According to the data, 79% of white students in England were awarded a 2:1 or 1st class undergraduate degree. The figure stood at 63% for Black, Asian and minority ethnic students. Despite the data showing a better average performance across all groups, there still was a 16 percentage point gap in England. When compared to an attainment gap of 9 percentage points in Scotland and in Wales, this highlights the importance of geographical context.

More recent data from the Office for Students (2020-2021) shows the persistence of the attainment gap. 87% of white students were awarded at least a 2:1 degree, compared to 81% of Asian and 69% of Black students. The 'awarding rate' has increased more for Black students than other groups since 2016/17. However, the attainment gap of 18 percentage points when compared with white students is still substantial.

This is the first of three reports looking at what causes the different levels of attainment in legal professional assessments across ethnic groups. The report details the findings from Workstream One, in which we have conducted an SLR. The SLR investigated what the academic and selected grey literature contributes to our knowledge of this attainment gap.

An SLR is a scholarly synthesis of published studies. It extracts and interprets data, then critically analyses, describes, and summarises interpretations. SLRs are commonly used in health care and public policy. This SLR has a broader focus on global data on education performance, as well as data on the profession, putting the assessments into a wider context. Therefore, the research question for the SLR was:

What does existing literature tell us about any attainment gap of Black, Asian and minority ethnic candidates in legal professional assessments?

The SLR does not provide solutions but informs our understanding of existing knowledge on attainment gaps relevant to our study. Armed with a broad knowledge base, we can then justify a focus on relevant details and environments, confident that important contextual information has not been overlooked.

Any priority area yielding limited results in the literature can be identified to be further investigated. The findings of the SLR help identify gaps and inform the design and specifics of the empirical research to be conducted in the project's second phase.

Findings from the systematic literature review

We took an interdisciplinary multi-level approach to the SLR to understand the attainment gap of Black, Asian and minority ethnic candidates in legal professional assessments. We used two major global databases to search for relevant Management and Organisation Studies (MOS) articles. Moreover, 19 peer-reviewed Law journals were chosen by the law- based members of the research team (for full details of the methodology, see Appendix 1).

Multiple search terms such as 'academic achievement', 'educational attainment', 'ethnic groups', 'ethnicity', and 'education' were used in search strings, giving an initial sample size of over 6,000 articles. The team did an initial scan of titles and abstracts, constructing relevant inclusion and exclusion criteria – for example, based on the quality and date of publication – which reduced the sample to 447 articles (272 law papers and 175 MOS papers). The team then read the full text of these articles, and again based on agreed inclusion and exclusion criteria arrived at a sample of 215 articles. These are included for analysis and synthesis in this report.

Open allThe 215 (99 from law journals and 116 from MOS) fully reviewed papers came from over 35 countries on five continents. The United States had the largest number of articles with 97 papers (45%), followed by the UK with 47 papers (22%). In total, the 215 papers came from 52 journals (14 from law and 38 from MOS). Within the law papers, 53 of 99 (54%) came from two journals, the Law Teacher and the Journal of Legal Education. Within the MOS papers, 45 of 116 (39%) came from one journal – the Journal of Vocational Behavior. In addition to management and organisation studies, the MOS articles came from disciplines such as psychology, sociology, economics and accounting.

We noted significant differences between law and MOS articles in terms of the approaches used. Doctrinal, conceptual and socio-legal pieces were common in law, whereas MOS articles adopted a more systematic approach to methodological, empirical and theoretical questions. In addition, MOS articles were almost all structured in a standardised format, allowing for easier searches. We tracked the number of articles by year since 2010, when the Equality Act 2010 (EA) came into force. In law, there was a steady increase over the 12- year period with 44 of the 99 (44%) articles published since 2018. Likewise, in MOS, 50 of 116 (43%) articles were published since 2018. For more details on the description of the sample, see Appendix I.

The four themes identified by the SLR were: the challenges of terminology; socioeconomic and educational background; professional and employment contexts; and interventions. In addition, a set of overarching themes describes the social mechanisms explaining the attainment gaps. These themes emerged as fundamental components of education pathways and practice settings. They also revealed differences amongst disciplines and divergence within and between countries. In the following sections, we set out each of these themes and the set of overarching themes.

Articles returned from the SLR revealed a wide range of terminology, categorisation and definitions regarding our focal point of interest - the attainment gap - and our population of interest. This is an important finding, demonstrating categorisation and definition issues. For our report, we will look at the attainment gap of minority ethnic groups but will comment on certain ethnic groups where these terms are used specifically in the literature.

Definition and categorisation of identities

The SLR revealed, broadly, four major approaches to categorising identity (using a variety of terminology): white/Black, ethnic minority, intersectionality, and socioeconomic status (including intergenerational mobility). These categories are used for different purposes, with different definitions and therefore have limitations, including issues of comparability, which will be elaborated on below.

Categorisation found in the SLR featured mostly in the context of the binary black/white approach. Categorisations differed by region. For example, a study from Brazil talked about different 'colour' descriptive categories as well as an Afro-Brazil category (Francis and Tannuri-Pianto, 2013). Other studies from the US talked about immigrant status and intersection with race/ethnicity (Dias and Kirchoff, 2021). A study from Australia talked about people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds and categories, for example, Aboriginal people (Lumley, 2015). Across the sample, there was a wide range of categorisation terminology used. For example: race, racialised, ethnicity, Black or black, Asian, Mexican, Latino, Latina, LatinX, African American, European American, Indian American, Nigerian ethnic groups, Aboriginal people, negro people, Han-minority, people from poor working-class backgrounds, minority ethnic individuals, BME, BAME, Black Asian Minority Ethnic, people of colour, disadvantaged backgrounds and marginalised groups. We have included in our SLR the term 'non-traditional backgrounds' because it evidences the complex ways in which economic, social and educational background shape future opportunities (Francis, 2015).

The black/white binary was critiqued across the literature covered in our SLR. One piece highlighted how this approach overlooks experiences of Latinas/os and other racial minorities, and how this shapes our conversations (Barnes, 2010). Another highlighted the challenges of operationalisation of ethnicity (Baskerville et al., 2016). For example, ethnicity and race are often conflated by many North American scholars, whereas many British scholars see race as objective and ethnicity as a self-determined subjective claim. As a result, while there might be a parallel debate on similar challenges, such varied approaches to concepts and theories hinder consensual dialogue (Baskerville et al., 2016). The multi- faceted dimensions of identity, beyond 'race and ethnicity' are recognised in the profession of counselling psychology. There, the term multicultural has been broadened to encompass dimensions of race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, age, disability, religion, and social class (Lee, Rosen and Burns, 2013).

Some literature chose other minority identity concepts and theories, which may include Black, Asian and minority ethnic groups. For example, one piece used the notion of 'racio- ethnicity', referring to differences marked by race and ethnicity, arguing that distinct classifications of these categories can lead to inaccuracies (Ruiz Castro and Holvino, 2016). Another piece spoke about notions and dimensions of culture (Vetters and Foblets, 2016), and another developed the concept of intersectional female ethnicity (Essers, Benschop and Doorewaard, 2010).

Intersectionality featured frequently in the returned literature (defined as multiple, overlapping identities which might occur when different factors interact and shape an individual's experiences and circumstances). For example, one piece focused on how gender, class, racio-ethnicity and culture intersect at the individual, organisational and societal levels to create and reinforce advantages and disadvantages across complex dimensions of difference (Ruiz Castro and Holvino, 2016). Another analysed the intersection between gender and social class and how this affected students' chances of being admitted to law school (Vetters and Foblets, 2016). Finally, a study focused on the variance by race/ethnicity and gender using SCCT (discussed in more detail in sub-sections 3.3 and 6.1) with STEM college students (Byars-Winston and Rogers, 2019). It concludes that an intersectional approach is needed because different combinations of social identities and cultural group memberships can lead to different lived experiences (Byars-Winston and Rogers, 2019).

In contrast to this work on intersectionality, a piece from the UK looked at the 'double jeopardy hypothesis' (Taylor, Charlton and Ranyard, 2012). This is a definition that intersectionality avoids because it suggests an additive assumption rather than a unique interactive identity associated with membership of different disadvantaged demographic categories. Another related term, the 'ethnic prominence hypothesis', argues for the salience of ethnicity over gender in perceptions. The smaller the numerical size of a social group, the greater the likelihood for it to be a salient aspect (Taylor, Charlton and Ranyard, 2012).

Several pieces dealt with Social Economic Status (SES), social mobility, and class – but these were often not defined or were used interchangeably. We perceive SES as a static measurement and social mobility as referring to intergenerational change. Furthermore, the review showed that US studies often use the term 'class' when referring to financial status. However, some returned UK studies used the term differently. See, for example, the following quote from one of the UK studies looking at ethnicity and class: 'middle-classness continues to be fundamentally associated with whiteness within the popular imagination.' (Archer, 2011, p. 149). While the notions of SES, social mobility and class go beyond categorisation along the lines of ethnicity, the SLR implies a relationship between class and ethnicity, as well as between social mobility and educational attainment.

Social mobility is about ensuring meritocracy through equal opportunities and vowing that people can reach their potential regardless of the circumstances in which they were born (Dursi, 2012). Social mobility can be measured by looking at socioeconomic background and by capturing data on parents' occupation and level of education (Social Mobility Commission, 2021). For example, one piece looked at class generally and the role of parents' socioeconomic status attainment on an individual's social mobility in later life (Shane and Heckhausen, 2013). Another paper examined the role SES of the family plays on the career aspirations of young children (Flouri et al., 2015), showing SES and ethnicity as determinants of aspirations (in boys).

Related to this, the literature looked at self-regulation theory and meritocratic beliefs about students' SES attainment (Hu et al., 2020). The Bridge Group – a non-profit consultancy that uses research to promote social equality – recommended lobbying for socioeconomic background to be a protected characteristic (Bridge Group, 2020). In Wales, in March 2021, the Socio-Economic Duty came into force. It aims at delivering better outcomes for those who experience socioeconomic disadvantage, though it does not apply to schools (Llywodraeth Cymru/ Welsh Government, 2021).

Definition of attainment gap

The terminology surrounding the gap in the attainment of different groups of candidates in assessments varied considerably. As stated above, in this report, we will use the term 'attainment gap'. This is the term used by the SRA in the call for this project as it is the most common in the UK. However, the term 'achievement' was more commonly used in other national contexts (Reardon, Kalagrides and Shores, 2019; Yang et al., 2015; Sáinz and Eccles, 2012). Other international pieces used terms such as 'performance' (Williams, 2013), or 'racial test score gap' (Katz, 2016). An article on legal education referred to legal professional assessment candidates as 'first time-passers', the 'never-passers' and the 'eventual-passer' (Yakowitz, 2010). Finally, another simply made reference to 'student success' (Farley et al., 2019).

Decolonisation narrative

With regards to the above terminology, it is interesting to note that some literature highlighted the preference for terminology surrounding decolonisation instead of 'racism'.

This might demonstrate a wider, contextual approach to understanding disadvantage, such as critiquing the system or the conditions faced by minorities. Decolonisation in this sense refers to acknowledging and (re-)examining the curriculum with regard to colonial influences. At the same time, it refers to redesigning the curriculum with the aim of eliminating racial hierarchies and creating a sense of belonging in academia for all. For example, one piece argued that racism, also within legal education is not segregation but colonialism, ie a system of power relations (Peller, 2015). Another argued that the 'decolonising discourse' is preferable to the gap narrative and looked at student-staff relationality (Raza Memon and Jivraj, 2020).

Furthermore, an article focusing on the decolonisation of university curricula noted that the Black, Asian and minority ethnic attainment gap is a very real and long-running problem, one that occasionally, by some authors, is erroneously just blamed on 'racism' (Matiluko, 2020). Decolonisation goes beyond rectifying representation and must include critiquing what is taught, how it is taught and why it is taught. It is about facilitating a classroom where all feel they belong and where debate and discourse is encouraged and connected to social realities of various groups (Matiluko, 2020).

A substantial portion of the current academic literature analysed in the SLR focused on aspects of background and education in the years preceding law school or law qualifications. These factors help expand our understanding of the context and underpinning social mechanisms that may influence the attainment gap later in life. Several studies also focused on the law school experience, with very few studies focusing on legal services qualifications as such.

Pre-school and school education

Several large US-based studies show that educational attainment gaps start at preschool (kindergarten) levels and remain throughout school years. Gaps are largest in high SES areas, due to the larger differentiation of resources available between the 'haves' and the 'have nots'. Preschool attendance is 'associated with enhanced reading and math skills, particularly for racial and ethnic minorities, children from lower SES families, and children whose parents were rated as less cognitively stimulating' (Tucker-Drob, 2012, p. 7).

US-based studies more commonly use the term 'achievement gap', defined as 'a proxy measure of local racial inequalities in educational opportunity' (Reardon, Kalogrides and Shores, 2019, p. 1166). Comparing differences between Black and white, and white and Hispanic children, Reardon and colleagues question the focus on the causal mechanism as either institutional education systems or socioeconomic and neighbourhood conditions (2019). They argue that this is a false dichotomy and that these issues are often inseparable. They also point out multi-level influences both close to (eg classroom interaction) and more distant from (eg neighbourhood economic conditions) the children (Reardon, Kalogrides and Shores, 2019).

A UK-based longitudinal Millennial Cohort Study examines the role the SES of a child's family and neighbourhood, as well as other contextual determinants, plays on the career aspirations of young children. These other contextual determinants include parental education level, maternal involvement and child's cognitive ability. By the early age of seven, family SES proves predictive of their aspirations, but with clear racial and gender differences (Flouri et al., 2015). A separate study of adolescents drawing on the Longitudinal Study of Young People in England, born in 1989/90, found that girls appeared more intrinsically motivated and less impacted by family background (Gutman and Schoon, 2012). Findings suggest that at a younger age, minority ethnic boys and boys from higher SES had more white-collar aspirations than white and lower SES children. They also suggest that in

England, seven-year-old boys' aspirations are directly shaped by their parents' educational, economic, and ethnic backgrounds (Flouri et al., 2015).

English language competence is understandably another influencing factor of educational results. A study considering six minority ethnic groups from the UK 2001 census (Black Caribbean, Black African, Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, and Chinese) measured preschool and during school achievement. In preschool, the minority ethnic children significantly underperform compared to the white British group. The study showed increased performance for most of the minority ethnic groups, except the Black Caribbean children, reducing achievement gaps during school years. However, much of the increased performance is explained by improved language capability, which also then explains the lack of increased performance from Black Caribbean children (Dustmann, Machin and Schönberg, 2010). Studies in other countries also confirmed the importance of ethnicity and language together (Frattini and Meschi, 2019; MacKinnon and Parent, 2012; Yang et al., 2015).

However, large studies focusing only on social mobility in the UK observe systemic barriers at every level of education and beyond (Dursi, 2012). For example:

- From birth, the link between socioeconomic background and future educational attainment is well established from literature prior to our review, with inequalities in educational capability evident from as early as 22 months (Feinstein, 1999);

- Throughout school years, gaps in linguistic and numeracy capability may be accelerated, with clear correlations between GCSE grades and socioeconomic groups. Strong links between low educational achievement and low school standards are also found, and a recent report by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (Chung, 2012) highlights increasing social segregation in UK state schools;

- A-level choices are also largely influenced by being in state versus independent education, which then further influences the choice of higher education institution and course;

- This carries through to university in terms of course and institutional aspirations and whether they are admitted. Law remains one of the most popular undergraduate courses in the UK;

- Data show a link between the university attended and earnings in law (Dursi, 2012; Francis, 2015). In addition, it has been reported that students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds graduating with identical qualifications are still less likely to secure levels of graduate positions or earnings equal to those of their wealthier peers (Dursi, 2012). This indicates that extraneous factors other than an individual's capability are impacting success and thus aspiration.

A large body of literature describes the multiple and multi-level factors that influence school educational achievement (eg Aucejo and James, 2019; Gutman and Schoon, 2012; Reardon, Kalogrides and Shores, 2019; Swisher, Kuhl and Chavez, 2013), including parental income (Wilson, Burgess and Briggs, 2011), parental education and class background (Feliciano and Lanuza, 2017), parental language proficiency (Schüller, 2015), geographical location (Gregory, 2013), neighbourhood poverty (Swisher, Kuhl and Chavez, 2013), family priorities and a country's economic context (Perez-Brena et al., 2017), gender attainment gaps within racial and ethnic groups (Lipshits-Braziler and Tatar, 2012), and the differences macro educational policies can make (Khanna, 2020; Taş, Reimão and Orlando, 2014).

Studies point to either direct effects of those factors or indirect effects – for example, mediated through career motivation or aspiration. In the UK and US, test preparation (for example, extra classes or tutoring) is found to significantly influence educational outcomes and is more available to children from affluent backgrounds (Buchmann, Condron and Roscigno, 2010). Although not within our review sample, in their book on social mobility, Major and Machin describe the UK's 'escalating educational arms race', with 'glass floors that limit downward mobility of those from privileged backgrounds and class ceilings limit upward mobility of those who happen to be born into poorer homes.' (Major and Machin, 2018, p.66).

Focusing on gender differences in adolescents and using the Longitudinal Study of Young People in England, with a cohort born in 1989/90, Gutman and Schoon (2012) find that young people from lower socioeconomic backgrounds and lower prior achievement (at age 11) were more likely to express uncertainty about their career aspirations (at age 14). However, their pathway model shows that the link between prior school achievement (at age 11) and later school motivation (at age 14) is stronger for boys than girls. The links between parental educational expectations, self-perceived ability, motivation, and academic performance show a similar pattern. This suggests that boys have a greater reliance on socialisation factors than girls. In other words, they are more affected by positive (and/or negative) feedback and (the presence and/or lack of) encouragement from parents than the more intrinsically motivated adolescent girls. Gender differences were also found within ethnic groups, with some ethnic groups fundamentally not supporting education for girls, for example. Additionally, gender differences can also be explained by socialisation due to lower overall expectations.

In Wales, a report on educational curricula experiences of Black, Asian and minority ethnic communities found the following, related to a number of factors, ranging from the lack of representation to negative lived experiences to decolonising curricula literature: '[…] the attainment of children and young people from some minority communities is being hampered by a curriculum that has failed to represent their histories, and the contributions of their communities, past and present. They are hampered by the lack of positive role models in an education workforce that does not adequately reflect the ethnically diverse profile of Wales; and they are hampered by experiences of racism in their everyday school life. This must change' (Williams, 2021, p. 4).

College/University

As with the literature on schools, the majority of the literature focused on differential achievement at college or university was based in the US. Whilst such findings may help inform our questions, we must be cognisant of the very different social histories that underpin race relations in differing countries (Opara, Sealy and Ryan, 2020). That there are attainment gaps in England and Wales is not in dispute. However, in the UK, the body of academic literature explaining the gap is perhaps less well-developed than that in the US.

Multiple US-based studies discussed differential rates of enrolment, experiences, success and completion for various minority ethnic groupings (Ciocca Eller and DiPrete; 2018; Brunet Marks and Moss, 2016; Owens et al., 2010). Moving away from measuring binary categorisations, panel data from American colleges shows that for various combinations of race, ethnicity and sex, having academic staff who match students' intersectionality leads to better student performance. Significantly, as a group became better represented, the importance of this relationship declined (Fay et al., 2021). This speaks to the importance of role models and representation of various characteristics in upper echelons, all of which impact culture and students' sense of belonging and identity (Adediran, 2018).

Other US-based studies, for example, by Hall and colleagues (2017) show how having a diverse friendship group moderates a negative association between ethnic discrimination and academic outcomes, acting as a buffer. Prasad and colleagues (2017) looked at the importance of multiple variables such as students' embeddedness, motivational characteristics ('grit' and self-efficacy), and perceptions of academic and social fit.

Compared to Caucasian students, research showed that minority ethnic students face additional challenges of embeddedness and academic fit with their disciplines, which may negatively impact academic outcomes (Adjin-Tettey and Deckha, 2010; Fouad et al., 2010; Tracey, Allen and Robbins, 2012; Urbanaviciute et al., 2016).

One response to minority individuals' lack of belonging or fit is to increase the representation of minority groups, either at an organisational or national level. For example, in the UK, partly in recognition of the additional challenges faced by 'non-traditional groups' at university, there is a focus on 'widening participation' (Gibby and Broadbent, 2015). This aims to increase the numbers and proportions of ethnic minorities, people with disabilities, and those from low socioeconomic backgrounds attending university, for example in law (Gibby and Broadbent, 2015; Waters, 2013), and other professions (Evers, Olliffe and Dwyer, 2017).

Interestingly, a number of studies from both the US and Europe looked at the impact of varying levels of diverse students on the performance of both the majority and minority groups with mixed results (Diamond and Huguley, 2014; Diette and Uwaifo Oyelere, 2014), white students often receive higher grades when in diverse student groups (Dills, 2018). One study found that universities tend to respond to student struggles with individual support rather than recognise that often 'inadequacies in resilience are social and institutional, and not personal failings or lack in the skill sets of students' (Ferris, 2022, p. 9).

While supporting academic and social development, research often fails to address the fundamental discriminatory attitudes that still exist among some institutions or people. For example, studies in higher education revealing persistent microaggressions and the perpetuation of stigma around race and class, show that 'paradoxically, the social institutions involved in' promoting social mobility 'conspire in the reproduction of both racial and class privilege' (Gray, Johnson, Kish-Gephart and Tilton, 2018, p. 1245; Carter, 2012).

In another example, a study of minority ethnic middle-class parents and children in the UK highlights this intersection of class privilege and racial subordination. Pay gaps between white and minority ethnic individuals are highest in middle-class professions and managerial occupations (Clark and Drinkwater, 2007; Archer, 2011). As has been found in prior research on gender in organisations, even when representational inequalities diminish, material and structural inequalities may still exist. Increasing representation is a good first step, but without cultural change, the benefits are limited.

As can be summarised from the literature briefly outlined above, the causes of attainment gaps are multiple and multi-level. Influences from outside of higher education affect individuals' performance within education. Following the approach set out in the HEFCE Report of 2015, we suggest that it is useful to consider differential outcomes that are underpinned by influences at three levels:

- The Macro Level: This is the wider context of learning, including both the structure of the English HE system and socio-historical and cultural structures such as those of race, ethnicity, culture, gender and social background that are embedded in the general environment in which universities, employers and students operate.

- The Meso Level: This covers the individual HE providers and related structures which form the social contexts within which student outcomes arise.

- The Micro Level: This is the level of communication between individual students and staff in the HE environment, including the micro-interactions that take place on a day- to-day level.

Law school

The attainment gap in higher education can be described as an incredibly complex social phenomenon (Bodamer, 2019; McKee, 2022). However, some suggest that less complex solutions are needed. Focusing on law school, Ferguson (2017) suggests that with a better understanding of some of the fundamental issues for what are termed 'non-traditional' law students, 'micro-adjustments' or 'nudges' can have a significant positive impact. For the purposes of this report, we use the term law school to mean higher education institutions that deliver a legal education either at undergraduate or postgraduate level.

Entry point issues

According to a recent book across school, university and the labour market, social mobility issues become most acute at the point of entry. (Major and Machin, 2020). Ferguson (2017) analyses factors of the Oxbridge application process for undergraduate law degrees and how the focus on A-level grades and on measurement of attainment is assumed to represent meritocracy. A-levels are only partially contextualised on application to university, by looking at the school but not at socioeconomic or poverty-related issues. These same grades are also used as the 'objective' measure of 'potential' or 'talent' when applying to law firms.

In a report for the Social Mobility & Child Poverty Commission looking at social mobility within legal, accountancy and finance professions, Ashley and colleagues explain that the qualitative attributes used in assessing students, such as 'drive, resilience, strong communication skills and above all confidence and 'polish' … can be mapped on to middle- class status and socialisation' (Ashley et al., 2015, p .6). Consequently, these attributes reproduce inequalities from social origin characteristics, such as class privilege and white ethnicity (Zimdars, 2010b).

The attainment gap of Black, Asian and minority ethnic students is a persistent problem. By the time all Black children in the UK get to age 17/18, regardless of their heritage, they are the ethnic group least likely to get accurate A-level grade predictions. In turn, this impacts the type of university they can likely attend (Rutter, 2013; Everett and Papageorgiou, 2011). In addition, as the figures above show, Black, Asian and minority ethnic students are far less likely to get a 2:1 or 1st class degree compared to their white peers. The situation refers to all subjects, including law, even when they enter with the same A-Level grades (AdvanceHE, 2019).

There have been various calls for widening participation in law schools, particularly noting that if this is not successful at law school, then obviously it will not happen within the profession (Fay et al., 2021). Recent UK figures show that 35% of students enrolled onto first degree law courses in 2021 are from a Black, Asian and minority ethnic background (The Law Society, 2022). Challenges include a lack of role models, aspirations, and opportunities (Balan, 2019; Levin and Alkoby, 2013; Moraitis and Murphy, 2013; Waters, 2013).

The discussion on widening participation is often bound up with that on positive or affirmative action (see the section below on Interventions). One question raised in a study of underprivileged law students in an Australian context was whether being identified as a 'widening participation student' would lead to them either being labelled or considering themselves as less capable. The study found no evidence that widening participation law students needed any additional support services if there was a well-designed and comprehensive programme that supports all students in the transition to higher education (Evers, Olliffe and Dwyer, 2017).

The HEFCE 2015 report also offered explanatory factors for the difference in outcomes. In the section below, we focus on the literature specifically about law and law schools using the HEFCE frame of explanatory factors (HEFCE, 2015):

- Curricula and learning, including teaching and assessment practices: Different student groups indicate varying degrees of satisfaction with the HE curricula, and with the user-friendliness of learning, teaching and assessment practices.

- Relationships between staff and students, and among students: A sense of 'belonging' emerged as a key determinant of student outcomes.

- Social, cultural and economic capital: Recurring differences in how students experience HE, how they network and how they draw on external support were noted. Students' financial situation also affects their student experience and their engagement with learning.

- Psychosocial and identity factors: The extent to which students feel supported and encouraged in their daily interactions within their institutions and with staff members was found to be a key variable. Such interactions can both facilitate and limit students' learning and attainment.

Learning and assessment in law school

Several studies, in the US and UK, have established that law school performance is a predictor of future career success (see, for example, Farley et al., 2019; Sander and Bambauer, 2012; Zimdars, 2010a). It is therefore important to look at the law school learning and assessment environment.

Learning environment

One of the most obvious aspects influencing the learning environment for students at law school is the homogeneity of the teaching faculty. Faculty often neither reflects the student bodies nor the population more widely (Fay et al., 2021; Sotardi et al., 2022; Vaughan, 2016). As in other professional environments, 'a diverse faculty is important not just so that students can see themselves in the people who teach, advise, and mentor them and be assured that there are faculty who understand their differences. It is also essential to advancing knowledge broadly and to pursuing ideals of justice in ways that recognize and include the experiences, aspirations, and needs of an even more diverse world' (Mann et al. cited in Segall and Feldman, 2018, p. 615).

Teaching standards and support structures within law schools inevitably shape how students think about themselves. They affect how much control and influence students believe they have over their learning throughout their academic journey (Sotardi et al., 2022). Learning is a social process, with interactions between teachers, students and peers critical to its success, and with the aforementioned interaction patterns influenced by race and ethnicity (Woolf, 2020).

Results from two studies in Australian law schools, as well as from a comparative one (Australia, Chile and South Africa), propose ways to achieve more inclusive and interactive learning environments. Some examples they use are the conscious use of case studies involving different socio-cultural groups and allowing more discussion of the implications of the law for different marginalised groups (Cantatore et al., 2021; Israel et al., 2017; Ricciardo et al., 2022). It is important to note here the focus on inclusion and inclusive education (De Beco, 2017) and not just the numerical representational goal of diversity.

Taking a more radical approach, Matiluko (2020) acknowledged the intersecting challenges, particularly of racially marginalised women in UK law schools. She calls for British undergraduate law curricula to bring 'an end to colonial continuities' in the ways that courses are taught (Matiluko, 2020, p. 547). Decolonisation, in the context of this report, does not refer to the material struggle – for example, land rights – but rather to institutional structures and practices which perpetuate the negative impacts of past colonial histories.

Decolonisation of curricula has become a common discussion point in UK higher education recently. However, as Matiluko points out, just talking about it is insufficient, law schools must demonstrate it 'overt[ly] in praxis' (Matiluko, 2020, p. 556).

Faculty could consider what knowledge is being produced, where it comes from, how it is taught, what power dynamics underpin it, and how more racially diverse students might relate to what is being taught. The academic literature is dominated by Western and Global North scholarship, and scholars' voices from outside of this hegemonic norm are rarely on the curricula. Voices from marginalised groups need to be heard in the classroom and all student backgrounds recognised as valuable in UK law schools.

Structural change is noted as being necessary to address the persistence of the Black, Asian and minority ethnic attainment gap and one clear way to address this is through decolonisation and curriculum reform (Universities UK and the National Union of Students, 2019). To prepare students to practise law in a particular jurisdiction, the course must teach the appropriate laws. However, teaching can recognise the roots of the laws and how they may perpetuate inequalities. Whilst maintaining the same content, teaching can include all voices meaningfully, and endeavour to create a sense of belonging for all. In turn, this would make what is taught meaningful for those students who might bring about transformational change in society (Matiluko, 2020).

In addition to teaching content, some studies focused on teaching styles or behaviours. For example, a study on the intersection between gender and social class in undergraduate law programmes in Colombia revealed how in-class experiences can perpetuate inequalities.

The paper described the 'hidden curriculum', meaning the different references of success and expectations, as well as levels of attention given to men and women law students and students of different class backgrounds by both the teachers and the institution, and how this can reproduce discrimination (Ceballos-Bedoya, 2021). Looking at how to address the attainment gap for Indian American women regarding success or failure of bar exams, Toya (2019) suggests teachers ensure safe spaces for minority voices to be heard. Additionally, institutional support should be in place to address technology poverty, which was particularly relevant during the Covid pandemic.

Assessment environment

The concept of stereotype threat has long been understood as a psychological threat experienced by individuals when in a social situation in which they feel at risk of conforming to a stereotype about their social group (Steele and Aronson, 1995). Most studies agree that whilst any students may experience test anxiety, minority ethnic students' performance on standard aptitude tests, such as the Law Schools Admission Test (LSAT) popular in the US and Canada, are particularly vulnerable to ethnicity-related anxiety or stereotype threat. One such study by Adjin-Tettey and Deckha (2010), which considered Aboriginal and other Canadian ethnic and racial minorities, made reference to earlier work in the US that observed 'something intrinsic to the structure or process of legal education affects the grades of all minorities' (Clydesdale, 2004, p. 737).

Much prior research in the gender field (outside of the scope of this review) has pointed to women having to 'overperform' to be considered as equal to their male colleagues in male- dominated environments. This also includes having more and higher-level qualifications.

Social explanations for this include the requirement of 'potential' not being as recognisable in individuals who do not 'fit' the expectation of what someone in that role should be like. This may be relevant to any assessments requiring social interaction, eg verbal examinations (Russel and Cahill-O'Callaghan, 2015). However, written assignments or exams may also present particular challenges for underrepresented groups.

The aforementioned challenges are often framed as 'writing problems'. In this context, an Australian study suggested that students should be purposefully acculturated into particular different styles of legal writing, rather than assuming they will intuitively pick them up (Moraitis and Murphy, 2013). As another study notes: 'If students from traditionally underrepresented groups require greater ability and effort to achieve the same results as students from traditionally overrepresented groups, then the entire system of assessing students from before admission, through law school, at the bar exam, and after may be systematically undervaluing the achievements of those students' (Strand, 2017, p. 201).

Moreover, Bansal, in an interesting study looking at how the Covid pandemic forced an immediate change in the exam format of UK law schools, noted that '[a]ssessment provisions within legal education in law schools in England and Wales are characteristically traditional – possibly to the point of archaicism' (Bansal, 2022, p. 355). Due to the online requirements of the pandemic, traditional closed-book exams (CBEs) were swapped for online open book ones (OBEs). Arguments for CBEs (that they are reliable, assess individuals, allow moderation, and incur little academic misconduct) are said to be founded only 'on a false belief that traditional law exams are superior to alternative assessments', as opposed to on sound pedagogical and education principles (Bansal, 2022, p. 357).

Bansal argues that the disbenefit of test anxiety, affecting 'behavioural, cognitive, and affective components, which ultimately weakens academic performance' (2022, p. 357) is greater for racial and minority ethnic students, who also 'feel inadequately prepared for traditional forms of academic assessment at university (eg CBE)' (Bansal, 2022, p. 357). This can lead to greater dissatisfaction with their assessments in comparison with their white peers.

The study suggests that the combination of teaching aimed at CBEs but ending up being assessed with OBEs leads to the disbenefits of both (Bansal, 2022). The paper questions whether UK law schools will revert completely to CBEs, or whether OBEs were found to have made any difference to the potential bias suffered by Black, Asian and minority ethnic students – evidenced by the persistent attainment and satisfaction gaps (Universities UK and the National Union of Students, 2019). The important point is that the pedagogical approach (design, delivery, formative assessment) is aligned with the assessment approach.

Relationships between staff and students

Belonging and community of practice

'Law students who feel as though they are being cared for, respected, and encouraged by law school academics in law school will likely see greater potential in themselves, and experience a sense of belonging and empowerment' (Sotardi et al., 2022, p. 85).

The importance of a sense of 'belonging' (socially and academically) emerges as a key determinant of student outcomes across several studies in the literature. A large body of sociological and social psychology literature explains the mechanisms behind this, for example, perceptions of stereotyping and bias (see, for example, Fouad et al., 2010).

Several studies from law schools reiterate the findings (for example Bodamer, 2019; Williams, 2013; Adjin-Tettey and Deckha, 2010). Interactions between academics and students can help shape which students succeed, as well as how and what they learn. Consequently, intervention strategies for creating and maintaining law classrooms that welcome, acknowledge and value diversity in the student cohort are suggested (see, for example, Adjin-Tettey and Deckha, 2010; Israel et al., 2017).

Minority ethnic students' 'perceived experiences of bias, discrimination, or unfair treatment, experiences of not being taken seriously in class, worrying that the professor underestimates their intelligence, and indicating that others would be surprised to see them succeed all significantly and adversely influence students' sense of belonging' (Bodamer, 2019, p. 477). This negatively impacts learning (Williams, 2013) and performance in law school even when controlling for demographics, enrolment status, past performance, and school controls.

Several studies discussed the important sense of working toward joining a community of practice within the legal profession (Balan, 2019; Ferguson, 2017). This is a challenging concept when you do not automatically relate to those within that community (for example, there are very few 'non-traditional' Queen's (now King's) Counsels – see Blackwell, 2015). An ethnographic study by a Black law professor speaks of the additional challenges and stereotypes Black people experience, and how law schools have both perpetuated racism and have an important role to play in remedying it (Gadson, 2019).

Recent law school literature acknowledges that since the problems may be caused at a system level, therefore the solutions should also be applied at that level. For instance: 'A lack of training contracts is not counteracted by an arms race in CV drafting. A lack of community is not cured by working on one's social skills. A sense of meaninglessness from chasing opportunities for social mobility that are rapidly disappearing is not resolved by developing a positive attitude to repeated rejection' (Ferris, 2022, p.14).

Psychological safety

The feeling of not belonging or feeling unwelcome in law school may stem from not feeling safe (Bodamer, 2019). Literature outside the scope of this review has previously defined psychological safety as when individuals believe they can be themselves and fully contribute without fear of negative consequences for their self-image, status, or career (Kahn, 1990).

One paper highlighted how maintaining a psychologically unsafe environment disproportionately affects minority ethnic students and further perpetuates systemic issues of race and ethnicity (Lain, 2018). The situation provides a better opportunity for those in the majority to succeed as lawyers. The paper gave an example of a race-based case study discussed in the classroom with very few minority ethnic individuals and the 'numerous levels of racialized interaction that were compounded by the class demographics' (Lain, 2018, p. 784). It also drew on an earlier study wherein students of colour struggled with racialised incidents in class (Sue et al, 2009), noting that 'they felt their integrity being attacked, they were fearful of the consequences of the conversation, and they were exhausted at having to deal with microaggressions' (Lain, 2018, p. 785). A lack of psychological safety can harm all students, but minority students may be 'adversely affected on a more significant level' (Lain, 2018, p. 787).

Social, cultural, and economic capital

In their 2015 report, HEFCE referred to the inconsistencies in students' experience of higher education dependent on their levels of social, cultural, and economic capital. For law students, this includes, for example, how they build, maintain, and use networks both within and outside of the law school, how they draw on external support and how their financial situation affects their learning, engagement and performance (Glater, 2019).

Studies in the USA caution against identifying students potentially at risk of underperformance primarily through their race, as race and socioeconomic factors are too intertwined. However, it is also acknowledged that Black and Latino students face financial constraints and social dislocation more than white and Asian students (Soled and Hoffman, 2020). In addition, in the USA, men also receive larger law school tuition discounts than women (Merritt and McEntee, 2020). 'Students from a lower socioeconomic bracket may have to assume paid employment during the tenure of these intensive courses, in addition to other commitments, and thereby compromise their test results' (Adjin-Tettey and Deckha, 2010, p.181). This Canada-based study shows how performance impacted by financial circumstances contributes to reinforcing stereotypes of Aboriginal and other racial minority law students as intellectually inferior. As with the above US-based study, it recognises the intersectionality of economic and racial status negatively affecting academic performance and, therefore, life chances.

A sociolegal paper by Chien, Mehrotra and Wang (2020), looking at who gets the most prestigious clerkships, found: 'three critical inflection points in the pipeline for clerkships that may contribute to potential racial and gender disparities in judicial clerkships (1) law student/applicant decisions based on perceptions, preferences, and ambient signals; (2) institutional support from law schools through faculty and staff engagement with the clerkship process; (3) and selection decisions made by judges' (p. 539).

As further explained in sections below, applicant decisions, expectations and ambition levels are influenced by their own and others' prior attainment.

Two UK studies, one based in a post-92 university, and the other in two post-92 and one Russell Group university, identified many complex and intersecting issues as impacting students' performance, with students identifying work experience as key (Childs, Firth and de Rijke, 2014; McKee et al., 2021). Of course, non-paying internships are even less accessible for financially less privileged students (see, for example, Grenfell and Koch, 2019, study of Australian legal internships and Sommerlad et al.'s 2010 report). Most forms of work experience at the Bar in the UK (itself a part of the legal sector very much lacking in diversity) are unpaid (Bar Standards Board, 2018). Law students with financial disadvantages need to ensure relevant legal work experience is paid, often constraining opportunities.

Despite a reasonable amount of academic literature on the importance of social capital in the professions in the UK, there is little academic literature specifically looking at its impact on Black, Asian and minority ethnic law students' progression in the UK (for an exception see Sommerlad et al., 2010). US-based studies show how students referred to as 'non- traditional' may feel socially and culturally isolated in law schools (see, for example, Soled and Hoffman, 2020). A UK study highlighted the lack of social capital as a negative influence on any marginalised group in legal education (McKee et al., 2021). Another underscored the importance of networking and seeking advice from both career services and tutors (Childs, Firth and de Rijke, 2014). However, we know from other work in higher education that disadvantaged, or socially marginalised students are less likely to use such advice opportunities.

Citing Morley (2007, p. 205), Francis (2015, pp.182-183) points to how 'socio-economic privilege appears to be transferred onto the production and codification of qualifications and competencies, [ensuring that] social gifts are treated as natural gifts'. Strong academic qualifications were the starting point and employers look for 'other means of distinction' such as communication skills and confidence as noted earlier.

Francis (2015) showed that of UK law students from working class and non-traditional backgrounds 'the successful students were those who had understood the need for distinction and who had the cultural capital and intellectual ability to demonstrate it' (p. 183). This was more challenging due to 'deep-rooted structural constraints' (Francis, 2015, p. 194) of law schools in terms of supporting disadvantaged groups. The author also points out that graduates' social and cultural capital is further weakened by the lower reputational capital of the institutions they are much more likely to have attended. Focusing on the very elite UK law schools, Ferguson (2017) suggests targeted non-academic support for socioeconomically disadvantaged students, with a focus on integration into the 'community of practice' and the acquisition of cultural and social capital (Ferguson, 2017).

Psychosocial and identity factors

As we have seen in much of the literature returned from our review, in endeavouring to understand the complex social mechanisms that influence academic outcomes, we need to consider both individual identity and environmental/social level differences and how the two interact. For example, prior experiences at a social level of unfair treatment or lowered expectations of law professors towards ethnic minorities negatively impact student outcomes (Bodamer, 2019).

In management, organisation and vocational studies, SCCT is a well-established theory that explains the development of academic/vocational interest, the pursuit of career choices and the persistence and performance in that academic/vocational field. The theory focuses on how the individual's cognitive processes interact with their social environment to influence their choices and career development.

Predicated on Bandura's Social Learning Theory, it focuses on four cognitive variables: 1) self-efficacy beliefs, 2) outcome expectations, 3) interest and 4) goals. It was originally conceived by Lent and colleagues (2010). A large body of literature has since developed, focusing predominantly on gender differences, but also on some minority ethnic samples, entering STEM careers (mostly engineering, academia or medicine).

One of the findings from SCCT work on women and ethnic minorities (not in law contexts) is that due to their marginalised and often vulnerable position, negative experiences tend to have more profound impacts on self-efficacy than on the male white majority (see, for example, Cadaret, et al., 2017; Dahling and Thompson, 2010; Ezeofor and Lent, 2014; Flores et al., 2021a; Lent et al., 2010; Sheu et al., 2018; Lent et al., 2018). Whilst at least 40 of the papers returned in our literature search touched on aspects of SCCT, we found no studies testing SCCT in the legal context. Moreover, none focused on ethnic minorities and professional post-graduate qualifications. This reveals an obvious gap for future research.

We did find one very recent paper taking a social-cognitive approach to legal students' studies across three New Zealand law schools. Taking account of the personal characteristics of the law student, the academic engagement behaviour and the law school environment, the study used longitudinal survey data measuring psychological distress, interest in a legal career and satisfaction with law school. Findings showed clearly that increased interest in a legal career is linked to greater confidence in performance expectations at law school (Sotardi et al., 2022). The perception of the law student personal characteristics focuses on achievement motivation, including: interest in legal career, academic self-efficacy, effort expectancies, subjective task value, satisfaction with law school and subjective wellbeing. Student engagement behaviour includes: lecture attendance, amount of group study, and amount of self-study outside of lectures and tutorials. The law school environment includes: support provided by staff, assessment manageability, timing of assessments, and grade coherence (expected and received).

Legal qualifications

The SLR did not result in many articles directly tapping into the realm of legal professional qualifications and/or assessments, especially in connection with ethnicity attainment gaps. Several authors focused on changes that might be brought by the SQE (Guth and Dutton, 2018; Hall, 2018; Davies, 2018; Bailey, 2018; Nicholson, 2022). Due to the SQE not being in the remit of this project, this section focused on any pertinent information the literature could provide to answer the research question of Workstream One. In regard to the latter, the literature highlighted the following issues:

Disconnect between qualifications and entry into the profession